|

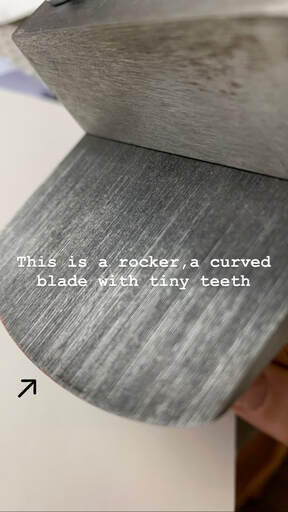

I was recently interviewed for a podcast in Italian ( out soon) and I thought I could write down my questions and answers for English speakers. How much time does it take to prepare a plate ? This is always the first question I get but I feel it is not much of an issue. Mezzotint is well known for taking a long time but egg tempera or photorealism in oils too are laborious techniques. Making a mezzotint shouldn't be presented as an heroic endeavour: yes, rocking a plate is a zen practice but you can also be more prosaic and catch up with the latest Netflix series ! So my answer is simply that it takes the time it takes, and I enjoy every minute of it ! For those who want numbers, rocking a 20x25 cm plate takes about four hours with a pole rocker ( see below). What do you use to rock your plates ? I rock my plates with two different rockers. I have a large 85 gauge (gauge means teeth per inch) rocker that does most of the work. I do about 30 passes with that one, in every direction. I then rock a dozen passes with a 45 gauge rocker. The pits that the 45 rocker makes are deep, hence the plate will yield more grays. Imagine a gray scale from black to white: you get more “stops” when you work with a lower gauge count. If used on its own the 45 rocker would need way more passes to rock the plate properly, and it's not a good choice if you want very fine details. By using two rockers I find that the surface is not as regular, once printed: dots and lines from rocking remain visible. This is what I want for my prints, but maybe it's not to everyone's taste. How do you avoid injuries when preparing the plate ? The game changer is my pole rocker ! Not only it makes rocking easier but also quicker by about a third. I strongly recommend the one engineered and produced by the french artist Remy Joffrion as it is very versatile. The end of the pole is mounted on a tripod so it can be easily moved around and adapted to any table. There are two different ways of placing the hand while rocking and it works with both hands. Remy has even tested it with the help of a physiotherapist to improve the ergonomics. It is also important to take frequent breaks while working to relax your arms and shoulders. (note: Remy’s website is a little outdated, no web shop. You need to email Remy to arrange a purchase. The price is about 280€ + P&P: worth every penny !) How often do you sharpen your rocker ? I sharpen it whenever I start a new plate. If the plate is more than 15x10 cm I might sharpen it again half way through. I use a round sharpening stone with a few drops of water rather than oil. I also use a sharpening jig that keeps the angle of the blade constant. Julie Niskanen, who makes the jigs, has a "how to" video here. How do you bevel the plate ? Before I start rocking the plate I use one of my bevelling tools: I have one from Matthieu Coulanges (his tools are beautiful ! In time I built a collection of them) and one from Arteina. Once the plate is rocked I do a little more bevelling, then I file the corners with a fine jeweller file and finally I polish the sides with a burnisher. I recently found that the ceramic sharpener I use for my scraper also works as a file/burnisher for bevelling.

0 Comments

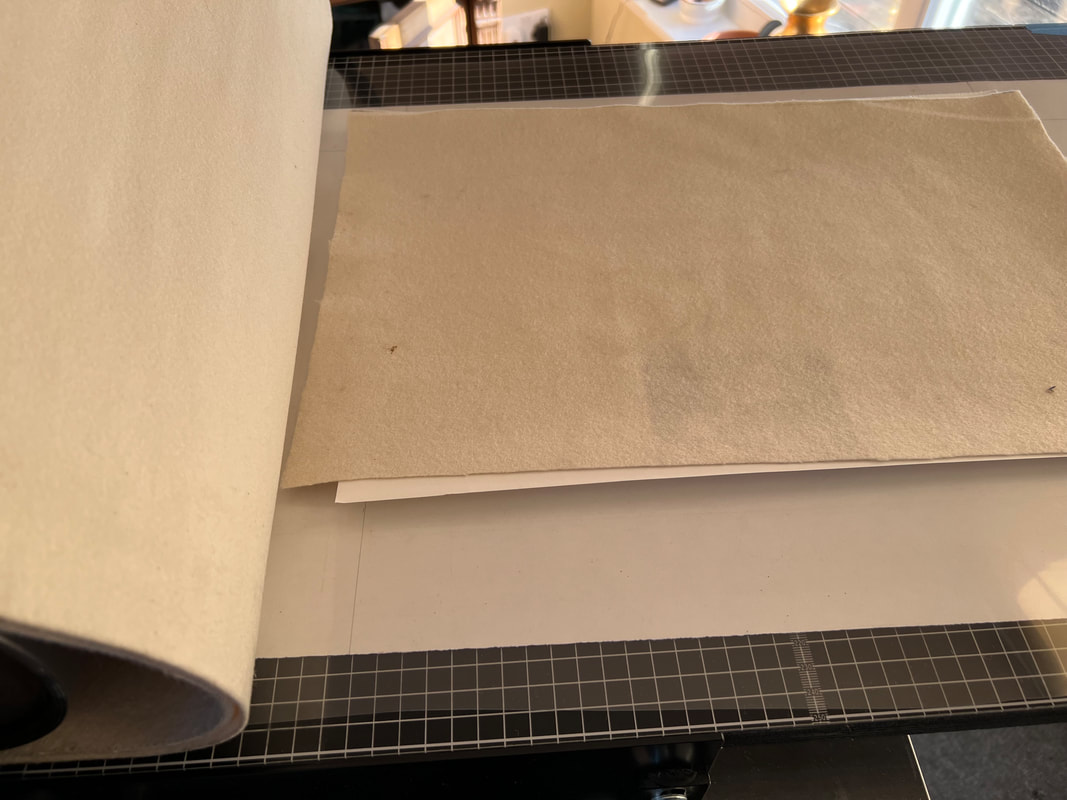

Printing a mezzotint plate is not the easiest thing: it took me a while to understand how to obtain the result I wanted, through trial and error (I've had very little printing tuition). I got some great tips from Mezzotint Essentials by Robert De Groff, a book I strongly recommend. What I understood is that the most common mistake is to overwipe the plate, but let's start from the beginning. My favourite paper is Hahnemuehle, and I use Charbonnel 55981 ink softened with a little plate oil, so that the consistency is a little runny. Aside from when I am printing a proof, I always prepare the paper making a damp pack two days ahead of a printing session: I quickly pass the sheets of paper under a tap, then let them drip the excess water and store them in a plastic sleeve inside a bin bag, then I leave it under a board with a book on top. If done well, there is no need to blot the paper before printing: it will be damp but not shiny ( if shiny, it does need blotting before it's used).  The ink should flow from the palette knife. The ink should flow from the palette knife. I use a disposable palette for mixing ink and a bit of cardboard for spreading it, so there's less cleaning afterwards. I also use clear plastic gloves for handling the plate and a different pair of gloves for handling the paper: no need of scrubbing the hands clean for every print. Something else to prepare beforehand is the registration sheet. Somehow the bottom of my plate is always filthy ! I draw the placement of plate and paper onto a larger piece of paper that I place on the bed of the press, then on top of it I put on a piece of clear acetate that I can wipe clean after each print. This is convenient when I am printing different plates, so I just slide a different registration sheet for each size of plate under the acetate. I don't own a professional hot plate: this is my low tech plate warmer. The plate should not be too hot that you can't even hold it, just warm. Once the surface is covered with ink I start wiping with a circular motion with the classic ball of tarlatan, and when the image appears I change motion to a swipe. As soon as the bulk of the ink has been removed, I take my gloves off and finish wiping with the palm of my hand, gently stroking the plate and wiping a little more with my fingers in the lighter areas. I don't use any chalk powder on my hand, I just wipe it on the apron before and between passes. I clean the sides of the plate with a piece of cloth on which I spilt a few drops of alcohol then place the plate on the press bed. I then wear the clean printing gloves and carefully place the paper over the plate, then a piece of tissue paper on top as well as an extra piece of felt to add pressure. I have two blankets in the press, a light swanskin and a medium felt. I set my press tight: it's not a geared one, so I use all of my body to turn the wheel. And voila. The prints go in between cardboards and under a pile of books for a couple of days so that they dry flat. After printing I clean my plates sprinkling Zest It (citrus solvent) and brushing with a soft toothbrush and again with alcohol ( methilated spirit).

Oh, and I was forgetting the most important advice: give it a day ! Or at least a couple of hours. If you are printing the first proof, don't rush to clean the plate and start scraping everywhere again. A print always holds an element of surprise when we lift the paper off: allow the first proof to "sink in" and see if maybe it might suggest a slightly different direction,or level of finish. Maybe some precise detail is not needed, or the scene needs a little murkiness, less contrast, softer edges. Look at the proof with fresh eyes and be open to change your original plan. What is mezzotint ? Mezzotint is a printmaking technique where the surface of a copper plate is worked with special tools in order to produce an image. The technique is part of a family of techniques called intaglio, where once the plate (matrix) is ready for printing and ink is applied, the ink will sit in grooves and pits lower than the surface of the plate. A mezzotint is an original print: this means that the print is not a reproduction of another existing artwork, like a digital print would be a photocopy of a drawing or painting for example, but is an original in itself. Original prints may be part of an edition; in the case of a mezzotint the edition generally is made of only a few dozens as the copper plate degrades after a certain number of impressions. Some mezzotints have larger edition because the artist has had the plate steelfaced ( plated with a thin layer of steel) which makes it harder hence more durable. The characteristic of mezzotint is that it is a tonal technique ( no lines !): the image is created by producing black, gray and white areas, and it is possible to obtain some very smooth transitions between these different shades. Mezzotint, also called maniera nera in Italian, manière noire in French and manera negra in Spanish, is well known for producing the richest and darkest black of all the intaglio techniques.

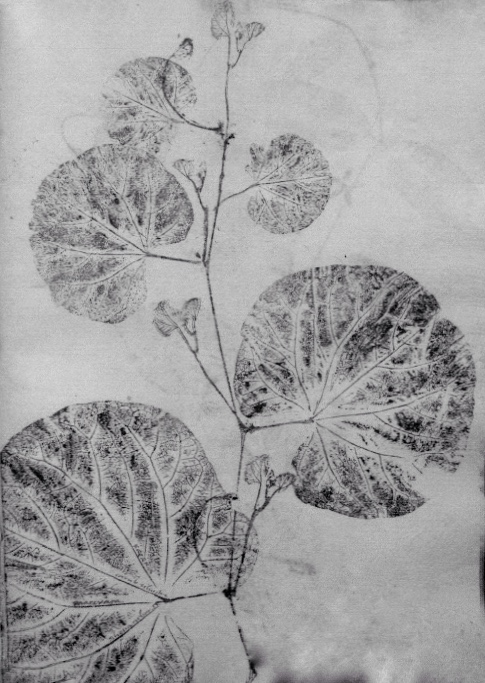

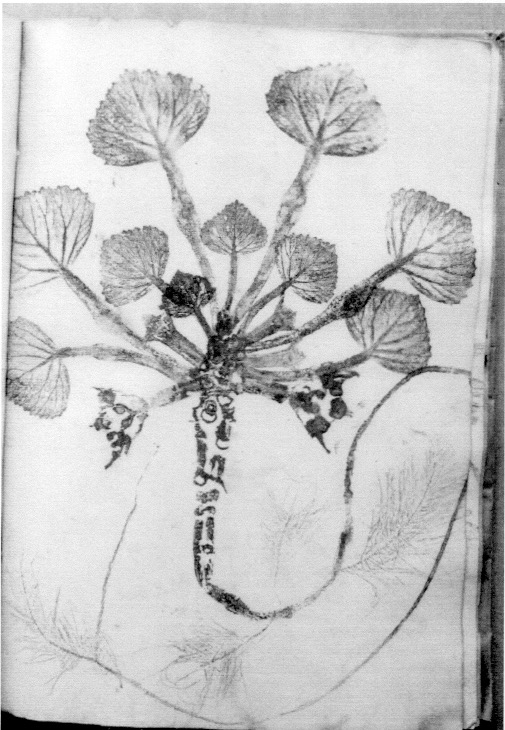

Mezzotint is a very laborious process as it needs a long preparation before the artist can even start working on the image. The plate needs to be roughened up with a special tool, called a rocker, that indents the surface with thousands and thousands of small pits that will later function as receptacles for ink. This preparation takes many hours, depending on the size of the plate. Once the surface is ready, in order to produce an image the artist has to scrape with a blade or smooth the metal with a burnisher so that the pits become more shallow (and will produce grays once printed) or disappear altogether ( for whites). This too is a lengthy process. Once the artist is happy with the image on the plate, it is time for printing it on paper. The plate is covered in creamy ink, which is then carefully wiped with a gauzy cloth and with the palm of the hand so that the excess is removed and the ink is only left in the pits. The plate is then placed flat on the bed of a printing press with a sheet of damp paper on top and as they pass under the roll the ink is transferred from the plate to the paper: the image finally appears in black and white. I am very excited to finally share with you a project that I have been working on these past weeks. You might already know how, as a EU citizen, I found the UK political situation of the past three years quite upsetting. As the uncertainty was coming to an unescapable end I set out to make my first artist book as a personal response to events. The book features five of my mezzotint engravings and it's made completely by hand in an edition of 4. Here below is a short video filmed by Alberto Lais. Hortus was conceived as a small Herbarium of Mediterranean plants that I collected on my street. They make the street more beautiful and diverse, and particularly the large olive trees have surprised me for how well they adapted to this colder ( less so now perhaps) climate. The parallel with my own life was obvious and it sparked a series of mezzotint engravings that I titled Immigrant Plants. The idea of collecting these in an artist book came when I learned of a herbarium put together by my ancestor, the pharmacist and botanist Stefano Rosselli, in 1575. I wrote about this extraordinary object here.

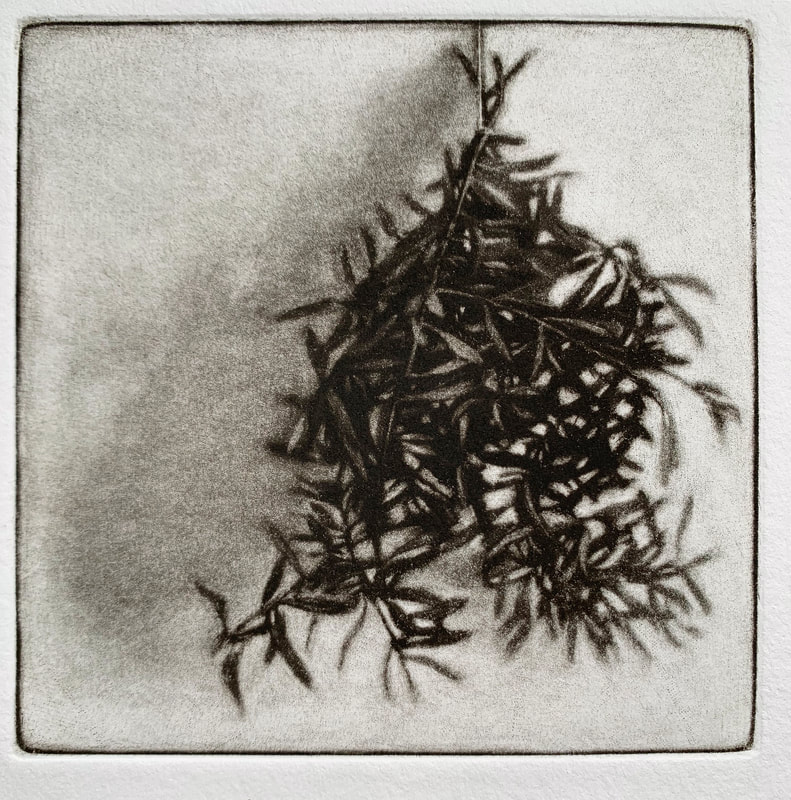

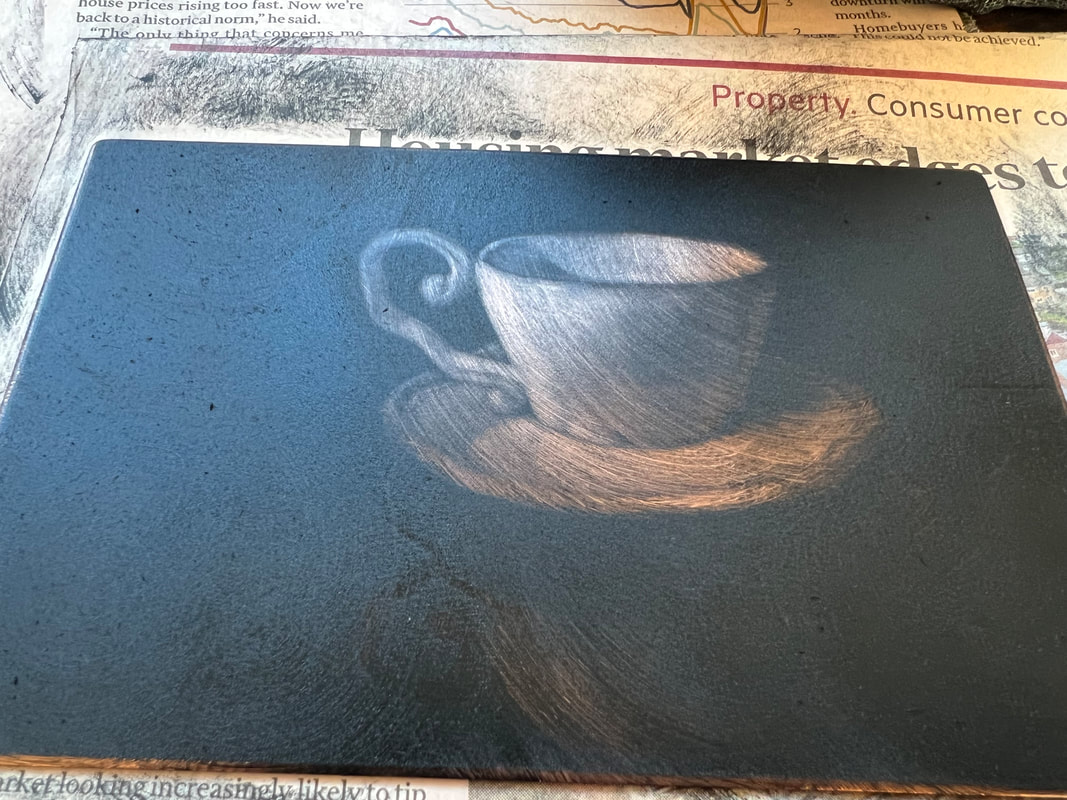

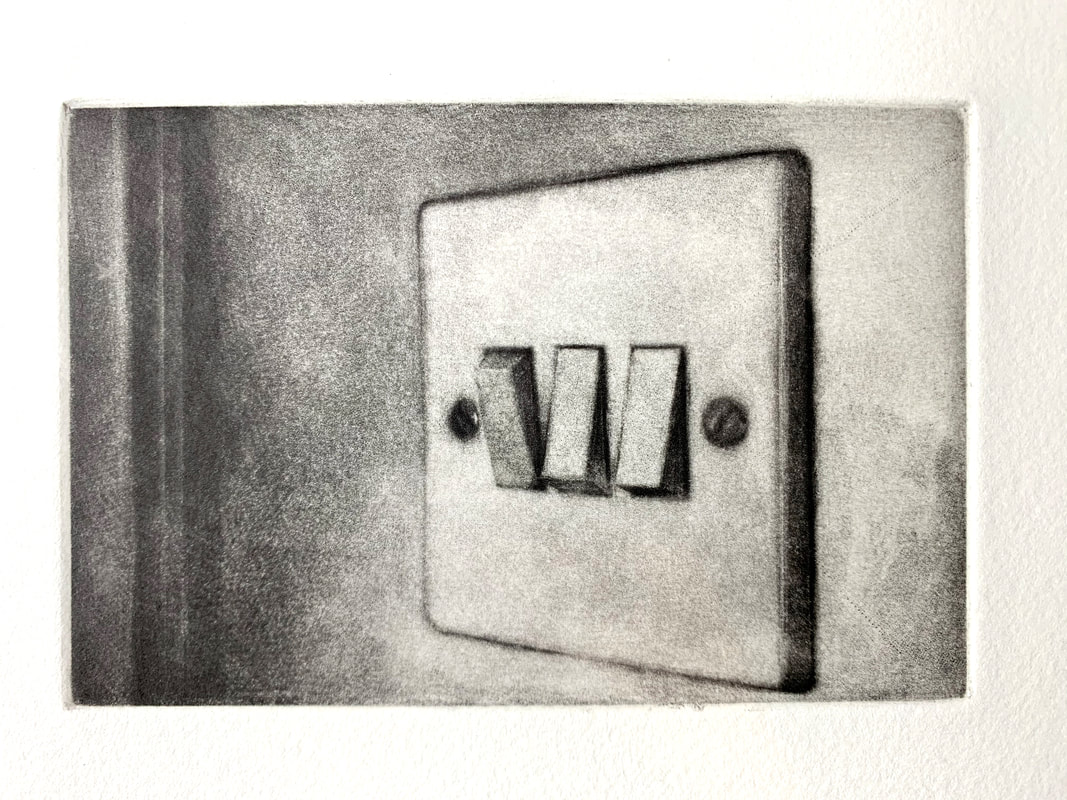

I am pretty stubborn and I wanted to make the book on my own, so I set up some sessions with book artist Mark Cockram. He showed me how to bind the pages, set movable types for the letterpress text, and how to make a box, then sent me home to work. The books, an edition of 4 completed on the 31st of January, turned out exactly how I envisioned them ! Here's a breakdown of the process. Because of the time scale involved in the work, most mezzotints are relatively small. Mezzotint plates can be bought ready-made, but I find the process of preparing a plate very rewarding and ritualistic, and this ultimately somehow adds to the poignancy of the image.  At the start the copper plate's surface is completely smooth. Preparing it for a mezzotint means roughening it up so that it will feel like very coarse sandpaper.  The tool used for this work is a rocker: a metal blade that looks a bit like a herb chopper, but with tiny teeth, like a comb. Rockers exist in different sizes and also with different teeth "density": the most commonly used have a "teeth count" from 65 up to 100. I have a 45 and an 85. The lower the count, the more it takes to prepare the plate but also the more shades of gray one can achieve, because the pits it will form on the surface are deeper. The rocker needs to be sharpened regularly while preparing a plate, another skill I had to learn for this technique. My rockers are mounted on a jig or a pole rocker to help me achieve a regular movement and protect me from excessive strain during the lengthy preparation. It is still a repetitive movement that ends up hurting my joints so I can't do more than a couple of hours at the time. Here below is the actual rocking of the plate: The blade is gently rocked sideways and it slowly "advances" on the plate, leaving behind a series of microdotted lines. The plate is then rotated by a few degrees and the process repeated so that after the many passes (I do 40 to 50 passes) required to complete the preparation the surface is completely rough and lines are no longer visible. The plate is now ready. Should it be inked and printed at this point it would result in a black rectangle. It is time to start scraping the lights out. I draw the image on the plate in pencil and start working on making the surface smoother in the areas that will be lighter. The lights are buildt slowly and the darks are carefully preserved. The scraping movements are short and sharp in details while longer strokes are used for larger areas. Scraping produces some copper dust as it effectively removes a thin layer of metal at each stroke. While I work I use a softbox light to avoid strong refraction on the plate. Here below is an image of the print obtained from this plate, regrettably the photo does not convey how velvety the print looks on paper !

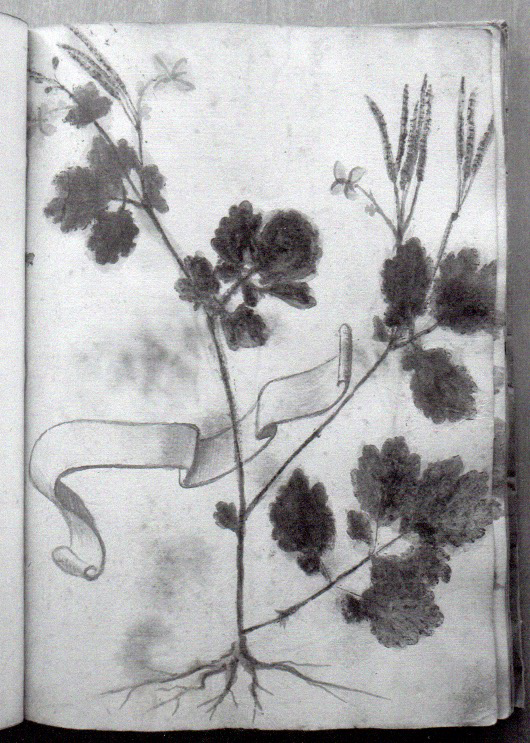

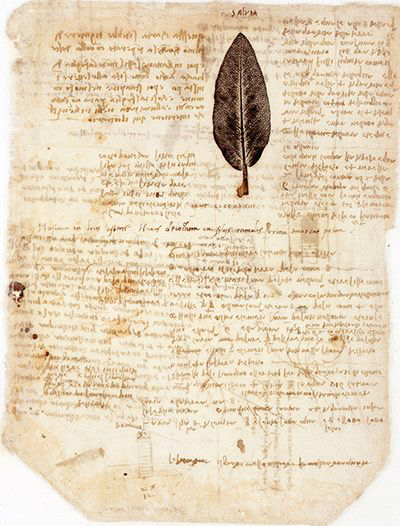

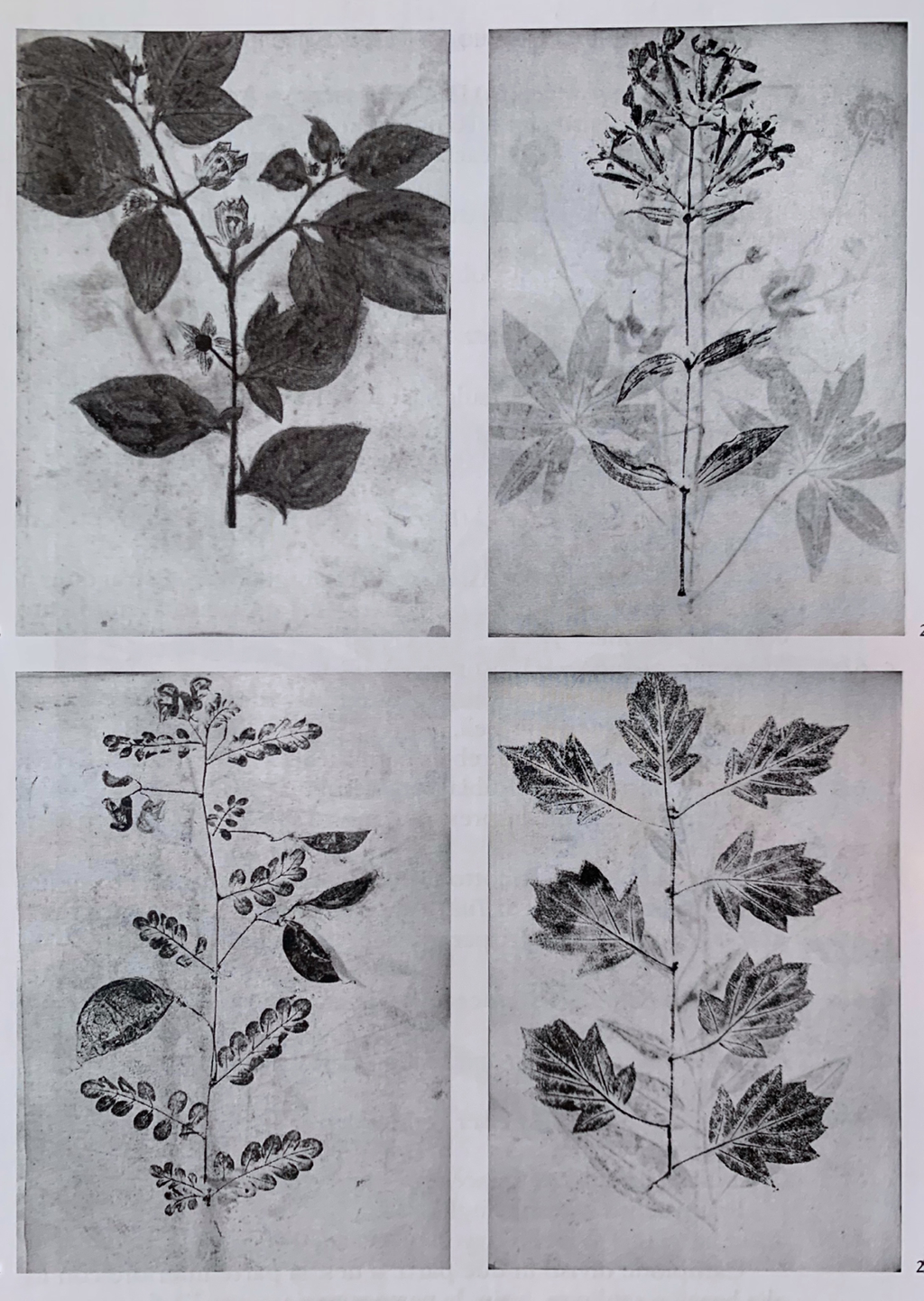

When I embarked in my recent series of mezzotints featuring plants, I didn’t know that I had some sort of precedent in my family. Through a research recently published by a group of academics ( G. Moggi, B. Biagioli, G. Cellai, L. Fantoni, P. Luzzi, C. Nepi) I’ve learned about an ancient book that is in my family’s library in Florence. The book dates from 1575 and is what’s known as Hortus Impressus, a text that presents a collection of plants The book was commissioned and annotated by an ancestor of mine, Stefano Rosselli. He was a “speziale”, basically a pharmacist. He had a flourishing bottega in Florence and his ointments and remedies where so famous that he became the Grand Duke Ferdinand’s pharmacist from 1588 to 1595. There are records of him being paid “three scudi a month and a horse”, and preparing antidotes for venoms, but also lip balm, for Cosimo I de’ Medici ( Ferdinand’s father) too. Stefano is also quoted as one of the pharmacists making the ultimate and true version of Theriaca: an ancient “omnimorbia poliremedy”, whose name derives from snake’s venom, that has been prescribed for over eighteen centuries as a potent medicine that could cure a number of diseases. The invention of Theriaca is credited to Mitridate, king of Ponto, and perfected by Andromaco the Elder, personal physician to the emperor Nero. Galeno cites 62 ingredients, that became 74 in Spanish pharmacology. In the 16th century the best Theriaca was made in Venice, where eastern ingredients could be added; these included opium, myrrh, cinnamon, gum Arabic, rhubarb, incense, turpentine and more. Stefano made his own version and was called as an expert consultant over the recipe in favour of the scientist and botanist Ulisse Aldrovandi in a famous dispute (they won) against the guild of physicians in Bologna. Going back to Stefano, with the money he made from his business he acquired a villa and planted a garden with all the botanic specimens he both personally collected and obtained through his contacts with the main botanists of the time, including Aldrovandi who is one of the fathers of modern botany. Stefano’s interest was no longer only medical, he became a passionate collector. In the Middle Ages botanical texts, compiled to document plants with medicinal properties( called Semplici), were illustrated with painted images (Horti Pincti). At the beginning of the XIV century botanists found a more reliable method by printing the specimens directly onto the pages (Horti Impressi). This practice lasted for almost two centuries before being substituted by collections of dried specimens ( Horti Sicci ). The most well known example of direct impression of a botanical specimen is a sage leaf found in Leonardo’s Codice Atlantico. Of course Leonardo’s enquiring mind was interested in this practice and he describes how a leaf has to be coated with soot from a candle, laid on paper and rubbed so that it produces an accurate image. Nerofumo ( lampblack) is the medium used for Stefano’s herbarium, while other books were made using inks or paints Stefano’s book is printed on paper with a Fabriano watermark. The first pages are made of a long list of plants copied from the famous herbarium of Andrea Cesalpino. It’s as if the list served as guide to then put together his own collection. The list is annotated in Stefano’s handwriting ( “thorny, grows in edges, diverging leaf but succulent, women call it marmeruce”, “maple whose seeds look like holmoak”). The second part, 83 prints, is the actual collection of prints, made of plants that could be found in Tuscany, both on coastal and mountainous areas and others more exotic that most likely came from his garden.

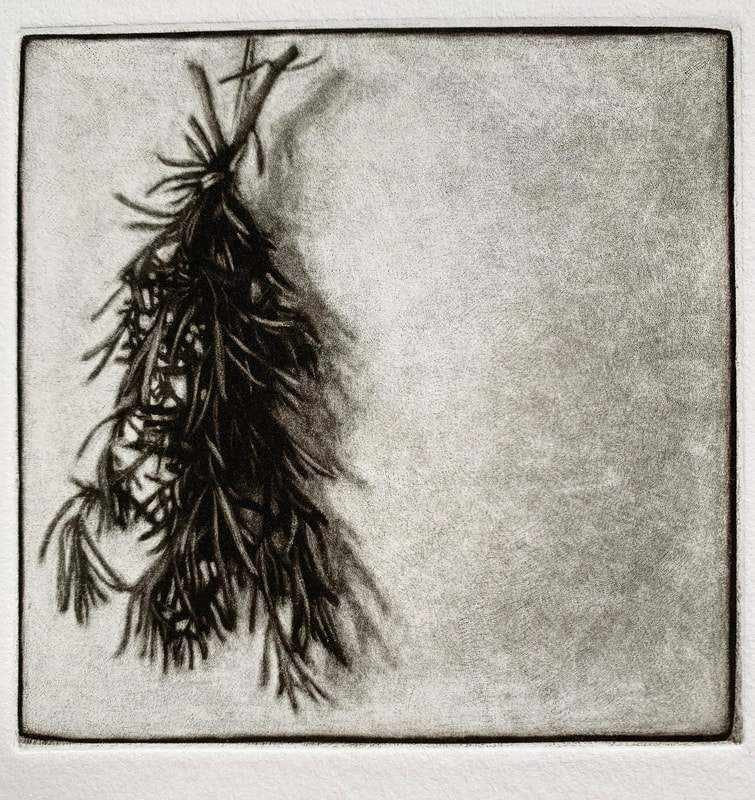

Some are arranged on the page in a very matter of fact way, some others end up with an interesting composition, some were even overpainted in watercolour. You can imagine my delight at finding out all these facts after having made plants prints, and I had unknowingly decided to use Fabriano paper for editioning them too ! The book doesn’t really have an artistic value, nor it’s a fundamental scientific text, however I find its amateur’s nature very endearing: it really feels like a personal project that was doggedly pursued despite being obsolete ( in 1575 the Horti Sicci were in use, and the codice Rosselli is the last known example of Hortus Impressus). It speaks about Stefano and his passion, and his tiny handwriting ( way smaller than the main copist) in my eyes betrays the seriousness and thoroughness of his character. Another element that filled me with joy is the amount of meaningful exchanges that Stefano has with his correspondents “abroad” (Italy was still divided in different states at the time). A case of an intellectual whose interests take him beyond national borders: he was eager to exchange and share knowledge with foreigners, and although his main interest lies in autochthonous species he wasn’t afraid of “contaminating” his own garden with alien plants that could increase the diversity and potency of his pharmaceutical concoctions. I've never been a political artist, however since my works are very personal it was inescapable that some current affairs were going to seep in. Here's a bit about me: I moved to London from Italy twenty years ago when my husband was relocated here - it wasn't a choice and honestly with three kids under five and having already moved three times in the previous five years I would have happily stayed where I was, but my reluctance was soon forgotten and my London life started. I definetely belong to the Easyjet generation, we live in a different nation from our family and old friends but then they are just a short flight away, we keep in touch easily, we can chat about the same TV shows, keep track of our holidays on Instagram. The word emigrant somehow sounds too extreme for me, it reminds me of people who settle far away from home and start a new life. My life is not too different from that one of my friends in Italy and I plan to go back at some point, I am probably more of a "semigrant", one foot here and one there, like many EU citizens I felt that the concept of home can be stretched by a couple of thousands kilometers. And then, here comes Brexit. During the campaign immigration was a big issue: EU citizens are evaluated for their contribution. Leave politicians paint us as a burden to UK society, Remainers advocate for us because we are workers, tax payers, consumers. All of a sudden I need a valid reason to live in Britain. I never thought of myself like that, reduced to productivity terms, I find it very sad. I believe that the benefits of freedom of movement in Europe go beyond the - well proven - economic advantages; they enrich our knowledge and further social progress, make us more rounded and empathic human beings without losing an ounce from our respective national identity. Through the past three years in my studio I tried to shut out this noise, but I wonder if my paintings have become darker, murky, and more doubtful. This past year my still life have included more plants, such as this painting of oleander leaves that I cut from a shrub I planted years ago at my front door. I had an idea for a mezzotint, using the same leaves for a simple composition in a square. It was during the long hours spent on that copper plate that I asked myself about the oleander. I planted it, it's personal. But why did I plant an oleander ? I remember just picking what I was familiar with. Oleanders are everywhere in Italy, and Italian kids are always warned not to touch them because they are poisonous. I also remember that I doubted it would survive English climate but surprisingly those few twigs grew to a very large shrub, they thrived here. Like myself, I thought. I immediately decided to start a series that I have titled Immigrant Plants, featuring mediterranean plants that I watched growing in u neighbourhood. I stole some olive branches from a tree that was inexplicably planted round the corner about fifteen years ago, an extravagant choice for urban decoration. The spindly sapling now has a magnificent twisted trunk. The rosemary is from my front garden again, where it bravely resists my carelessness. Some Bay leaves are in the works.  Immigrant Plants - Ulivo ( Mezzotint 12.5x12.5 cm) Immigrant Plants - Ulivo ( Mezzotint 12.5x12.5 cm) I miss the time when news weren't monopolised by the fruitless discussions about trade and rules. I hope to hear more voices that advocate for freedom of movement and for the merits of a diverse and multinational society and for the principles of cooperation and solidarity.

|

Check the list below to see posts on these subjects.Categories

All

AuthorIlaria Rosselli Del Turco is an Italian painter living in London. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed