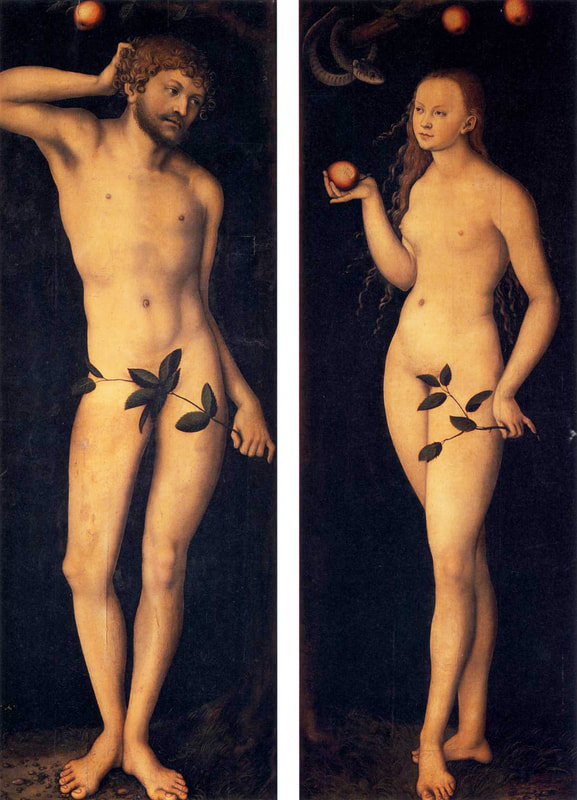

A few years ago he published a very entertaining and pleasant book, Il Museo Immaginato, where he plays at designing an ideal museum where he can hang any work of art. The virtual institution about which he fantasizes in the book, that would be designed like a house and include a kitchen ( with works by Zurbaran, Cotan, Campi, Rembrandt ), a cellar ( Velasquez, who else?), a dining room with paintings by Veronese, and so on. Do you want to appear as scholarly snob as Mr Daverio in his trademark bowtie? Clearly indicate your belonging to continental culture ? Here are some expressions I picked up in the book that you can carelessly drop in your arty conversation: HANCHEMENT ( or Contrapposto): the body posture of classic sculpture where the weight is supported by one leg ( Standbein, let's throw in some German too) while the other (Spielbein) is relaxed. Useful also to describe Cranach's postures. DRANG NACHT SÜDEN: it's the pull towards the South. Barbaric hordes felt the call to cross the Alps, and Goethe of course, but why not apply it to all the Gran Tourists and to the northerners dwelling in the Riviera, such as Matisse ? VERGISSEMEINNICHT: what? Do you call this humble blue flower from Durer's Adoration forget-me-not ? Then you wouldn't be referencing its importance in medieval German culture as a symbol of enduring love and, later, freemasonry. MENUS PLAISIRS : No, this is not found in restaurants, it's the part of a royal household that would have organised events and celebrations. The aristocratic personality responsible for the Menus Plaisirs was in charge, for example, of the design of porcelains or ephemeral decorations, fireworks and music. NICCHIO: that's a scallop, but not in its edible form. The Coquille Saint Jaques was the symbol of Saint James, it's were Botticelli's Venus stands and is seen in many architectural niches ( hence the name) both painted in trompe l'oeil or sculpted. Piero della Francesca has genially reversed it in his Pala di Brera and made it into a striking element from which an ostrich egg ( an animal that at the time thought of as hermaphrodite, so self-fecundating) is hanging. WUNDERKAMMER: of course you already know about this cabinet of wonders that was the favourite guilty pleasures of princes and dukes all over Europe. Who was the trend-setter? It was the typically prognathous Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II , who had withdrawn to his castle in Prague and was curing his melancholy with compulsive collectionism. FLOHPELTZ: It's that soft and luxurious fur worn by Parmigianino's young girl and many other painted ladies. It was used to attract lice and fleas away from the body and head. I confess I might have a jacket with a fur collar... seems much less nice now. ACCROCHAGE: You are not really still calling it the museum's "display", are you?

DAS LAND WO DIE ZITRONEN BLÜHN: Goethe again, speaking about Italy, the land where lemons bloom. Stick some French in your sentences and you are sophisticated, but try German and you'll be... übercool

4 Comments

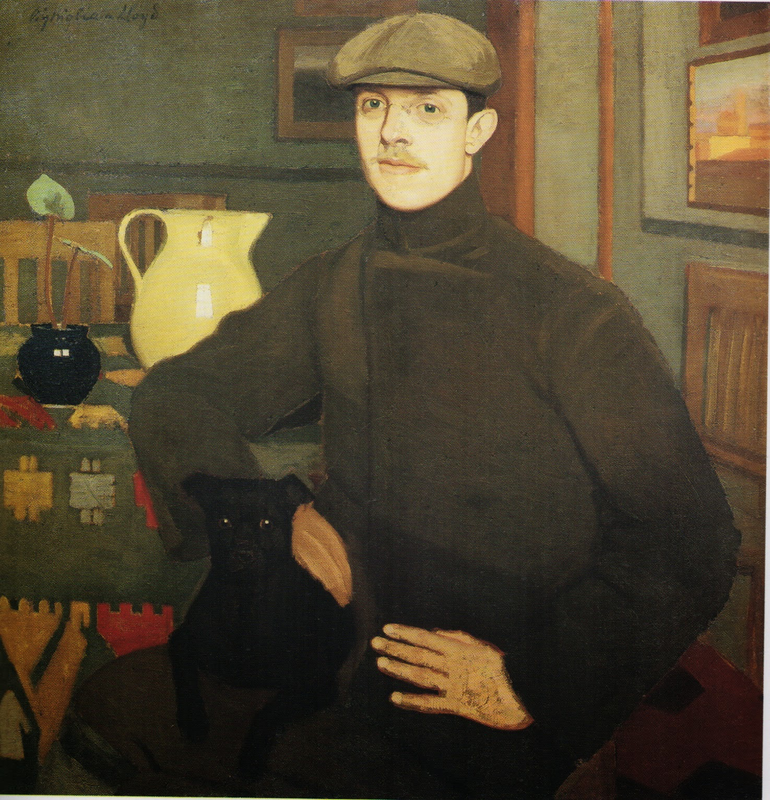

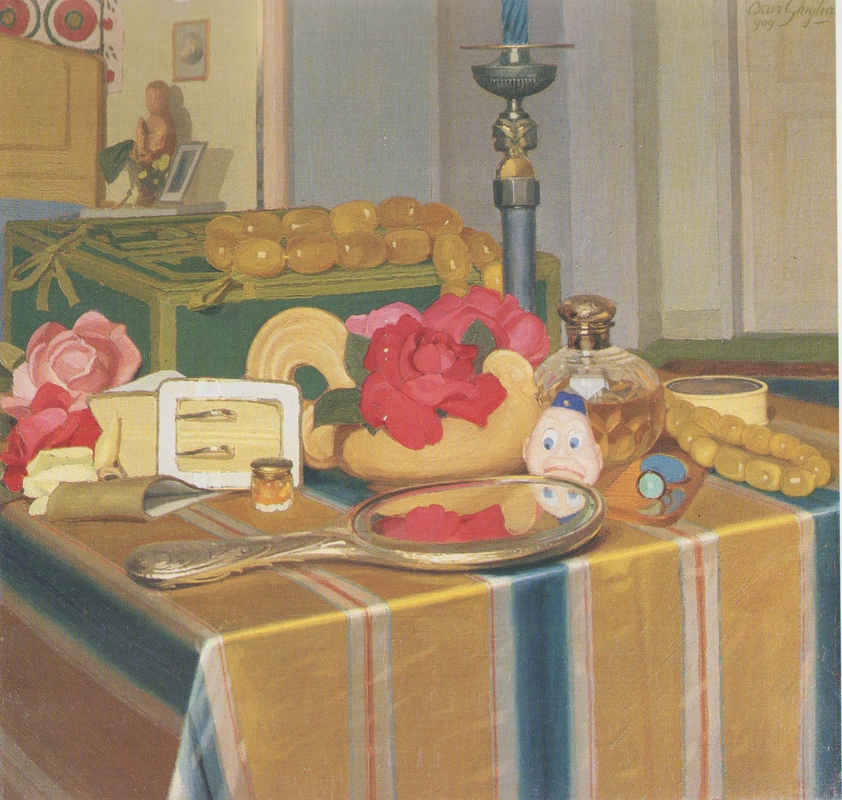

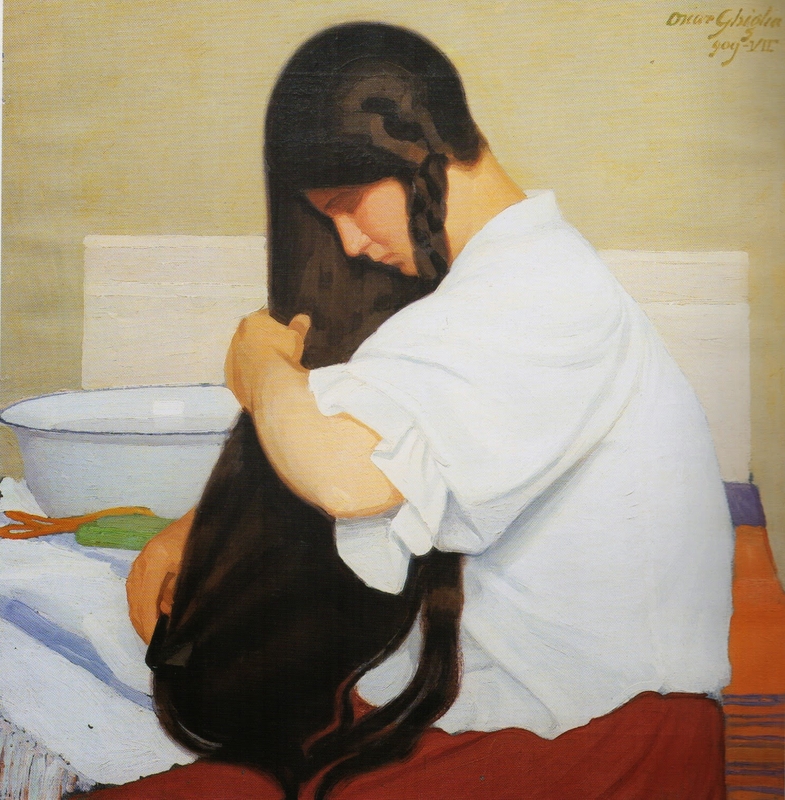

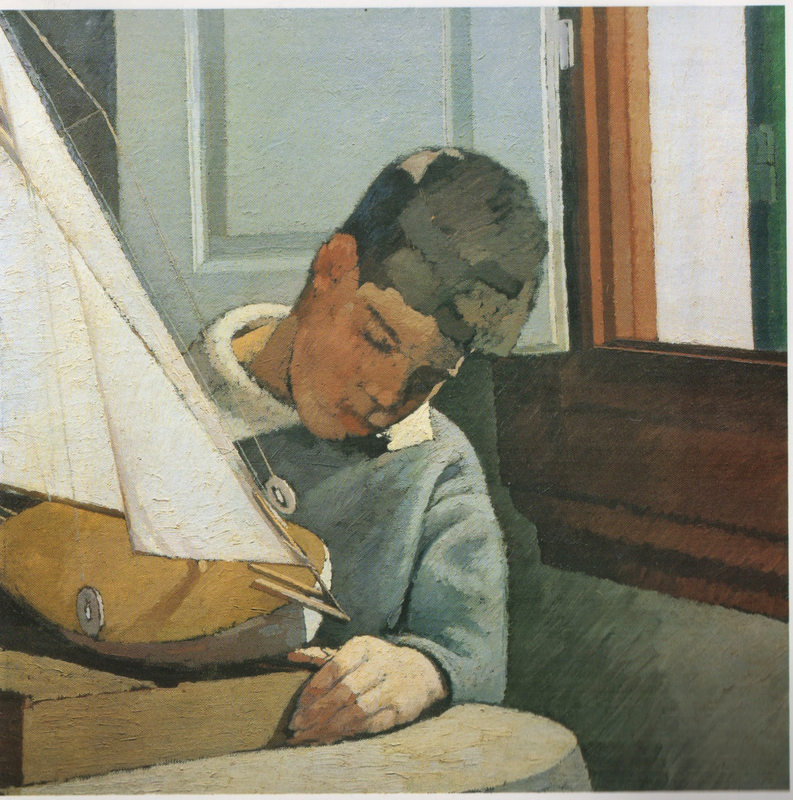

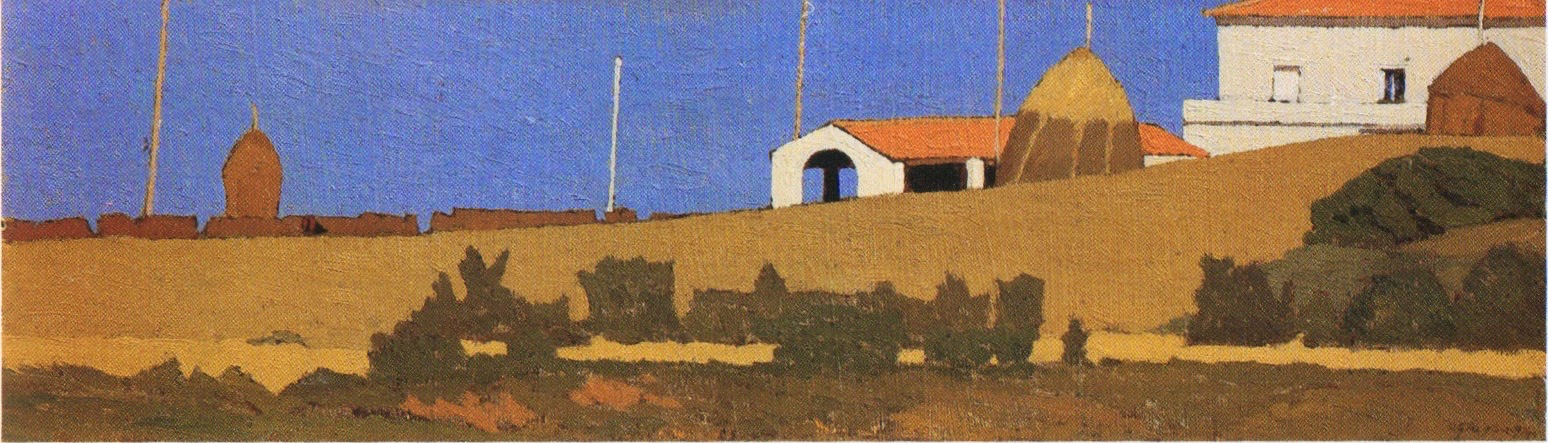

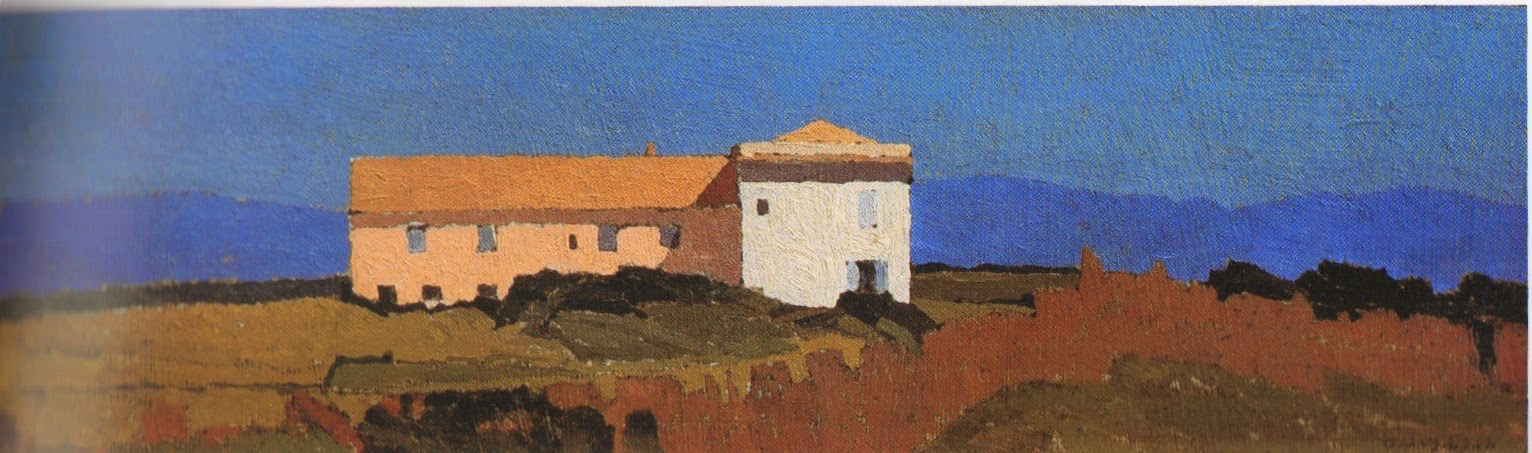

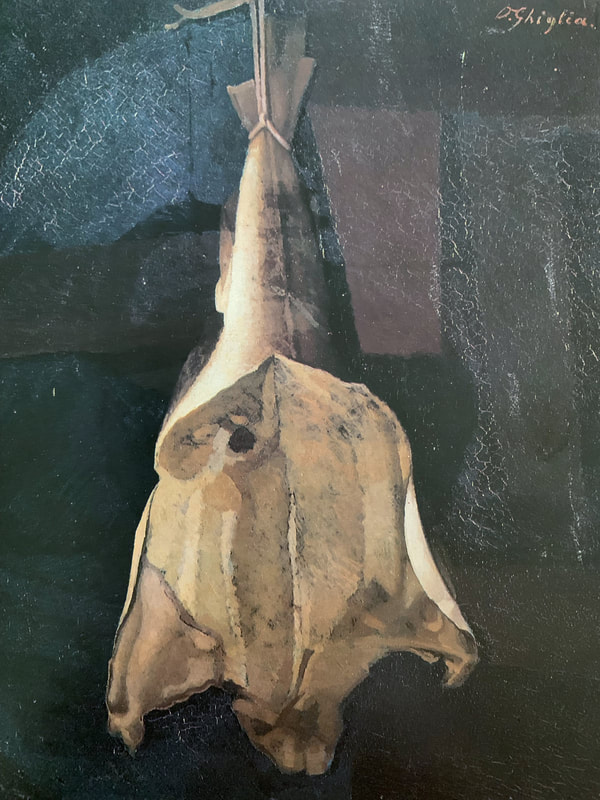

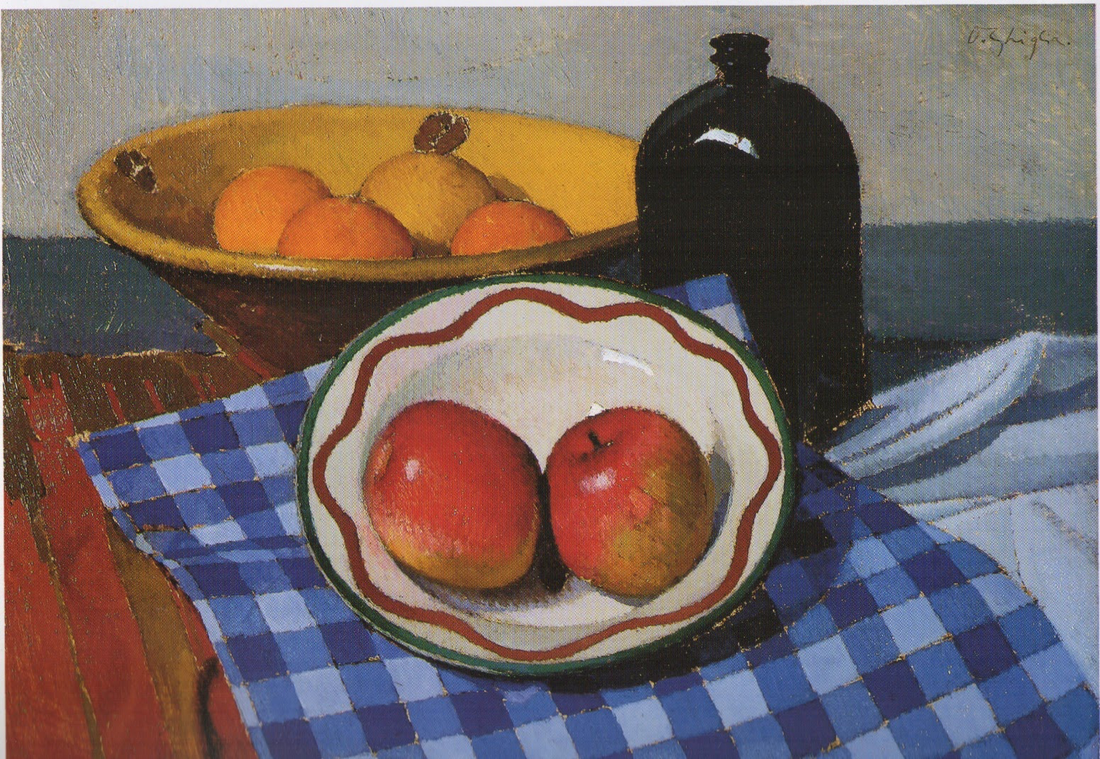

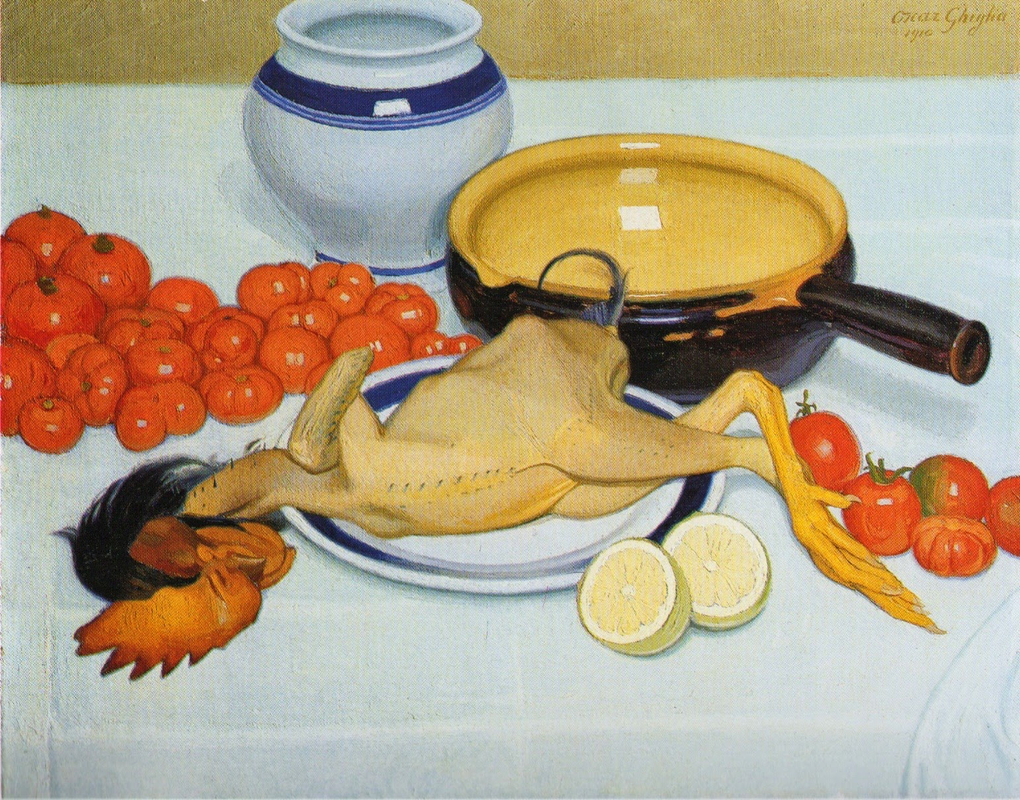

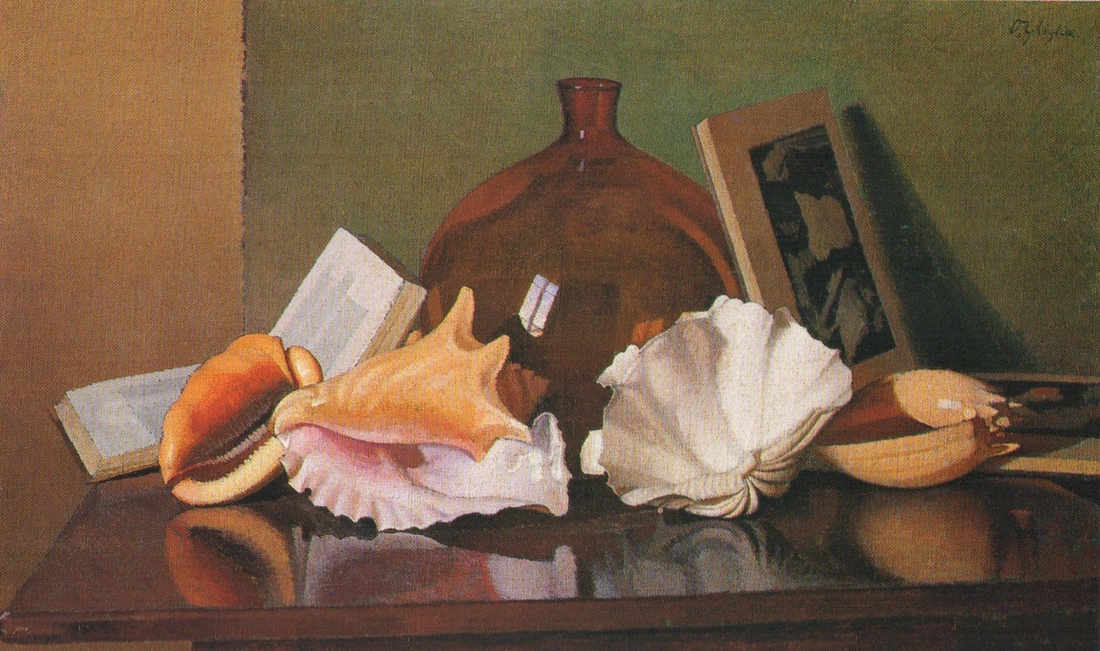

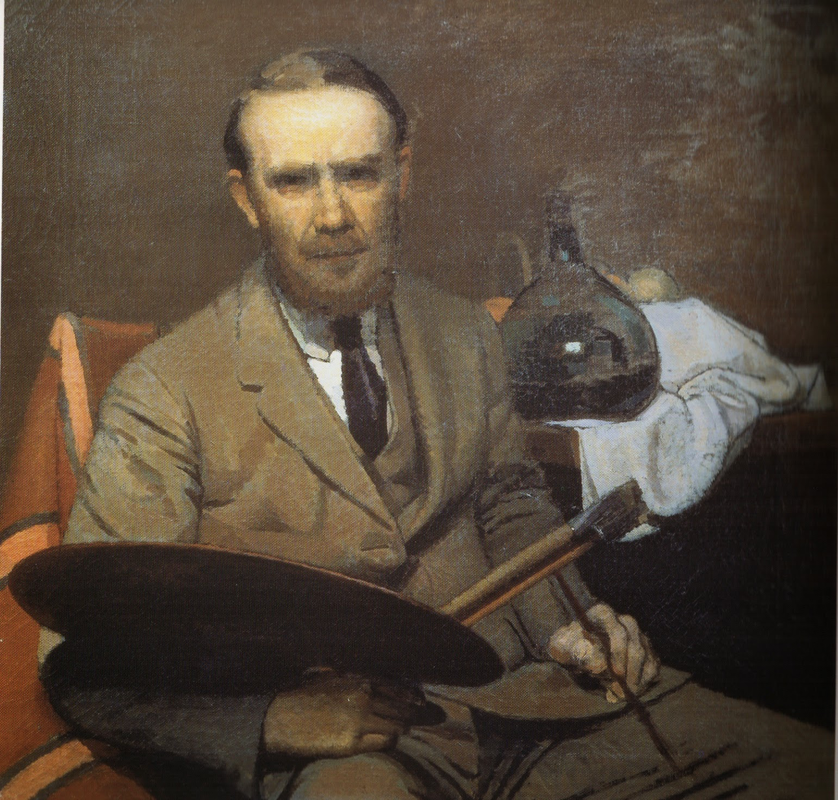

Oscar Ghiglia, A Forgotten Master I came across the work of Oscar Ghiglia in a visit to the museum of Villa Mimbelli in Livorno years ago. Since then I never had enough of looking at his work. Oscar Ghiglia, b.1876, came from a very poor family in Tuscany and lived in poverty for most of his life. He was self taught and started painting in his early youth while doing all sorts of odd jobs. In those years he lived in Livorno, a city on the Tuscan coast. Ghiglia was able to bravely overcome his humble origins and his lack of formal education, and became part of the cultural elite of Tuscany. He wrote that his sordid existance of the first years of his life "is when my character was being delineated, in that I always believed best to communicate with objects than people"- as an explanation for his love of the still life genre. In his youth he befriended the painter Llewellyn Lloyd and Modigliani, who was a little younger and from a very different background. Through Modigliani he came in contact with many jewish families to whom he was close and loyal for the rest of his life, including during the hard years of racial persecution. It was not until 1901 that he moved to Florence and started attending the Scuola del Nudo, led by painter Giovanni Fattori, the star painter of the time. Fattori respected him as an artist and they paid each other studio visits, but Ghiglia did not fully belong to his students' group nor ever ascribed to the divisionist painting language that many Tuscan painter were adopting. In Florence he also joined a group of intellectuals that included Papini and Prezzolini, who will eventually form the core of the Futurists. He was well aware of the social and political situation at the time however his art was deliberately apolitic, and he disliked the -isms of that time. He did not share the fascination for modern machines and speed that was at the core of Futurism, and later on openly condemned fascism and war. Another vital meeting of the end of the century was with his wife Isa: her devotion and affection supported him throughout his life providing the serene atmosphere that is so well depicted in his paintings. Ghiglia's artistic breakthrough happend in 1901 when his self portrait was included in the prestigious Esposizione Universale in Venice. In the meantime he was making real progress, studying the old masters preferring Titian and Rembrandt to the Florentines. His portraits are characterised by a solid perspective structure, immediate but in fact very complex. They never indulge toward sentimentality nor they become flamboyant. With a classical departure point, they are made modern by the simplification of the drawing; all the emotional content is reduced to a precise construction of the image. At the start of his career he mainly painted portraits but in the painting of his friend Lloyd ( above) his interest for still life is starting to appear. In these first years there is no evidence of contacts with European contemporary painting, particularly with artists who had interest in the domestic such as the Nabi or Scandinavian, nor William Nicholson, who were all shown in Venice too. At this stage his development was completely autonomous- although the friendship with Ojetti soon gave him access to the extensive library of this well-known intellectua, and Cezanne's influence can be clearly seen after 1910. In 1914 at the start of WW1 he finds a refuge on the coastal town of Castiglioncello with Isa and their five children. He experiences strong feelings of isolation, as he was seen almost as a bolshevic by the bourgeois holiday makers and far from the warmongering spirit of his frends, the Futurists. Here he will paint some beautiful landscapes that are integral to his work. The format and the subjects recall the Macchiaioli painters but landscape for him is in fact a rational construction. with solid brushwork, the opposite of "optical" impressionism, and an intuition of the surface as the field of chromatic relationships - like a mosaic ( in his own words). In Castiglioncello he will also paint still life and beautiful portraits such as Paulo with the Boat, above. After the war he goes back to Florence, where he witnesses with spite the rise of fascism. Figure comes back into his work, particularly the figure in the mirror, an object that will remain a favourite motif for the next decade. This period sees the resolution of his contract with the collector Gustavo Sforni, who had basically acquired the greatest bulk of his production. It was a relationship that helped him out financially for years but might have ultimately damaged the chances of his paintings circulating more widely. Now in his fifties and increasingly isolated also because of his antifascism, he continued to paint magnificently during the 20s and the 30s. In 1943, while he was an evacuee in the countryside, weakened by sickness, his house, many paintings and all his cast of objects that had appeared in his works were lost in the only allied bombardment of Florence in WW2. Ghiglia died in 1945. Info gathered from: Oscar Ghiglia, Maestro del Novecento Italiano, published by Farsetti Arte in 1996. LISTEN BELOW FOR THE CORRECT PRONOUNCIATION OF HIS NAME

If there's one thing I have to force myself to do is going to the gym. I know it's good for me blah blah but I find it utterly boring and I am so good at procrastinating that my morning session always happens around 7pm. Because of the random nature of studio days I don't go to classes, I rather do my thing and that's when listening to some engaging conversation has the magic power of keeping me on a tedious rowing machine beyond my first sweat. Enter the arty podcast, an audio program that is just long enough to last one gym session ( or a good walk). I like listening to podcasts when I am not in the studio, as some of them are so interesting that they distract me from painting, but some times while I work I listen again to the ones that I found more inspiring or motivating to see if they generate ideas or throw new light on the painting I am working on. I originally drafted this list for my old blog in 2015 and it is lovely that many are still going ! Here's my updated list : PAINTERS TALKING ABOUT PAINTING - Studio Break It's a new find for me, I got there following the guys from Printeresting, a printmaking blog, and had a look around to find two interviews with FB friend Joe Morzuch so started listening. The interviewer, artist David Linneweh is very good at conducting the conversation and asks the same questions I would ask. Update 2018: I since have been interviewed by David ! -Savvy Painter Features artists in conversation with painter artist Antrese Wood. She touches on practical aspects of painting such as promoting the work, as well as asking interviewees about their career path or their daily studio practice. Artists that have been interviewed include Israel Hershberg, James Bland, Stuart Shils, Mitchell Johnson, Stanka Kordic, Karen Kaapke, Dean Fisher and many others. -John Dalton Gently Does It John is another very good interviewer. His podcass feature many well known painters and are quite long so they go deeper into the conversation. John has also started a subscriber page on Patreon, asking for just a dollar a month to sustain the podcast: an easy way to donate. -Suggested Donation Generally focussed on classically trained artists, Only six women interviewees in more than forty episodes ! - Art Grind Podcast Long conversations among artists conducted in person by three interviewers, very nice atmosphere and interesting considerations. -Artist Decoded Host Yoshino interviews a variety of artists, not only painters. Urban feel. - The Studio- Interviewer Danny Grant also focusses mainly on classically trained painters. MARKETING FOR ARTISTS - Artists Helping Artists. Lots of tips to navigate social networks, ideas and tricks to be well organised in the studio, useful apps and more. ART HISTORY AND EXHIBITIONS National Gallery of Art (US) Great collection of lectures recordings from the NGA education programs. The Modern Art Notes Podcast Thoughtful interviews with artists, curators, art historians and authors Getty Art + Ideas A variety of interviewees often linked with current exhibitions at the Getty Museum. NO LONGER UPDATED BUT STILL AVAILABLE - The Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center Features a variety of artists in conversation with the art critic Peter Trippi. Includes artists such as William Bailey, Lois Dodd, Gillian Pederson Krag and my friend Alexandra Tyng. - The Royal Academy Features academic introductions to shows by curators or artists, interviews and conversations. The recent conversation between Tim Marlow and Frank Auerbach is probably THE perfect podcast. I hope you like my selection. Alternatively here's some cardio class entartainment: Sprezzatura is an Italian words but very few Italians nowadays would understand its meaning, although it sounds quite similar to "disprezzare" ( to despise) and "sprezzante"(contemptuous). The term was coined by Baldassarre Castiglione, an important character of Italian Renaissance, who was a political counsellor and the author of Il Cortigiano: a manual in which he outlines the characteristics of the perfect gentleman at court. The book, together with Macchiavelli's The Prince, marks an important shift in culture, when interest turns away from medieval metaphysics and turns to society. Il Cortigiano was one of the best-sellers of the century, and Francis I had it translated in French too. The book was written in Urbino between 1513 and 1524 and finally published in 1528, when in Italy courts such as the ones in Ferrara, Urbino, Mantua were at their peak. Courts were not only a centre of political power but cultural hubs where intellectuals, writers, poets, musicians and artists came together. In Il cortigiano, Castiglione talks about grace as the most important quality that a courtier should possess. The courtier is a gentleman who is supposed to know how to ride, lead a pleasant conversation, be a scholar, dance, dress up and have impeccable table manners as well as fighting skills. All these activities, says Castiglione, must be naturally performed without effort, and this is what sprezzatura means, a certain detachment and non-chalance that should dissimulate any strain; in Castiglione's words, make the viewer believe that one just can't go wrong. In the book he cites an example of a dancer who puts so much attention in what he does that he can be clearly seen counting his steps and is therefore an ungraceful and unpleasant partner. At the core of sprezzatura is not effortlessness though, but the ability at feigning it, the skill of dissimulating it. This is the other aspect of its influence on painting: bear in mind that the word "arte" in ancient Italian has the wider meaning of modus operandi, and it's at the root of words such as artifice. Sprezzatura is a behavioural quality of a painted sitter but the term can be also applied to the piece of art itself, made in a seemingly easy way and almost without thinking and with non-chalant virtuosism as if it sprang not from a long and arduous training and painstaking work but purely from natural flair. It was in those years that sprezzatura became a positive quality for the artist and nowadays we still hear the words "raw talent" enthusiastically spoken about as if the lack of effort or formal training was the most desirable characteristic. Roberto Calasso ( an Italian scholar) sees Tiepolo as a perfect example of an artist who practices sprezzatura: light and fluid touch, fast execution, confident and flamboyant brushwork.

|

Check the list below to see posts on these subjects.Categories

All

AuthorIlaria Rosselli Del Turco is an Italian painter living in London. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed