|

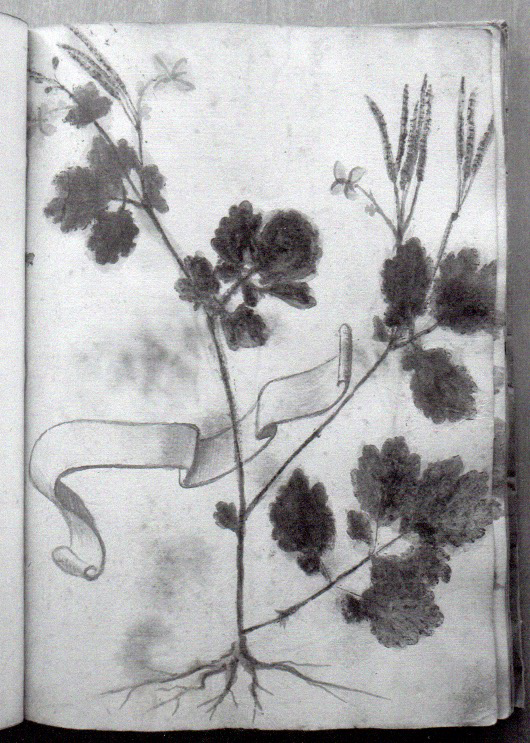

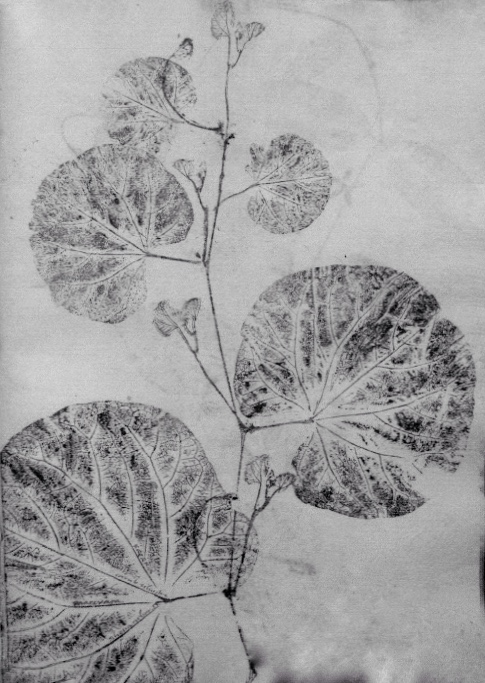

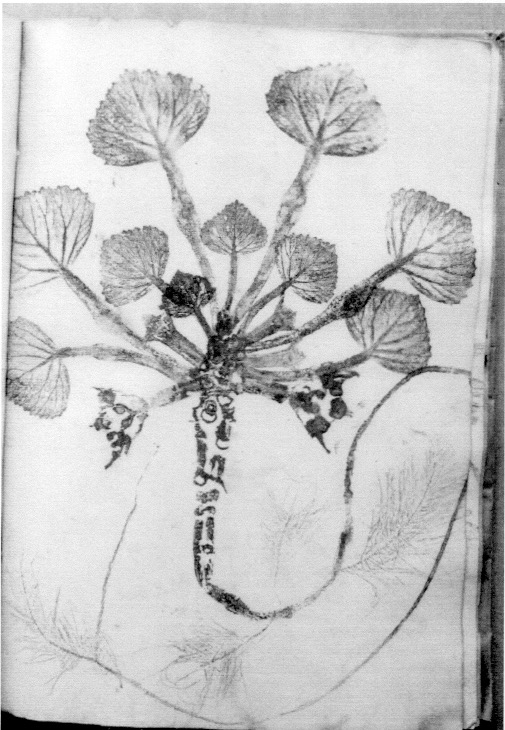

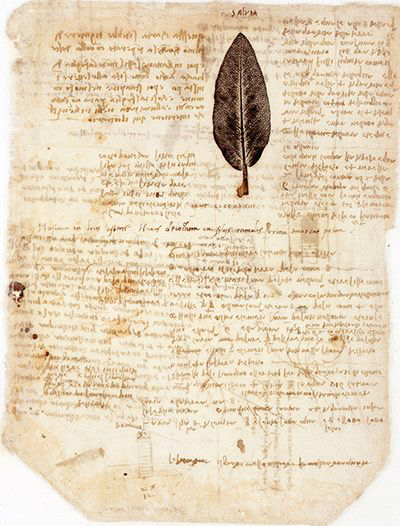

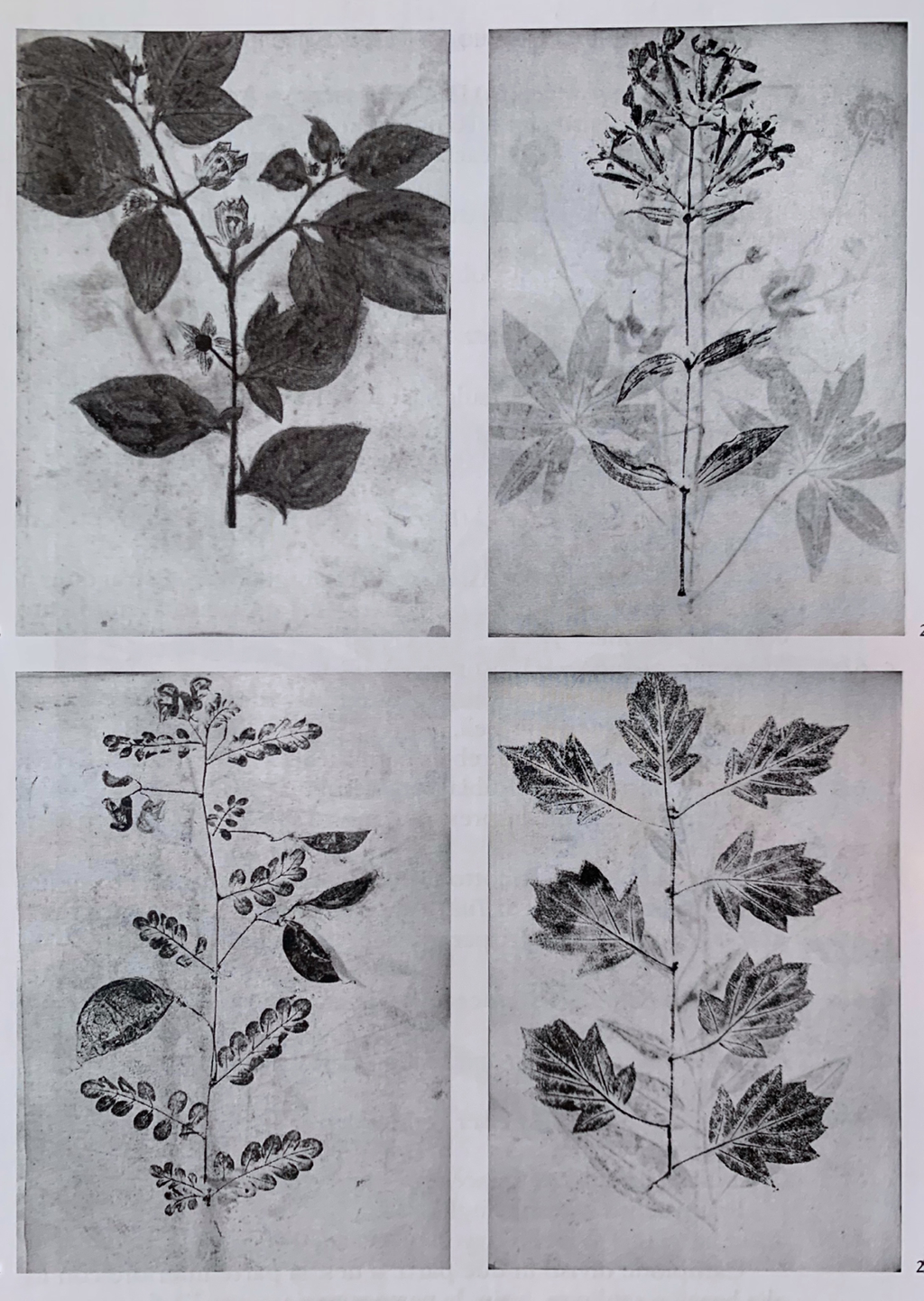

When I embarked in my recent series of mezzotints featuring plants, I didn’t know that I had some sort of precedent in my family. Through a research recently published by a group of academics ( G. Moggi, B. Biagioli, G. Cellai, L. Fantoni, P. Luzzi, C. Nepi) I’ve learned about an ancient book that is in my family’s library in Florence. The book dates from 1575 and is what’s known as Hortus Impressus, a text that presents a collection of plants The book was commissioned and annotated by an ancestor of mine, Stefano Rosselli. He was a “speziale”, basically a pharmacist. He had a flourishing bottega in Florence and his ointments and remedies where so famous that he became the Grand Duke Ferdinand’s pharmacist from 1588 to 1595. There are records of him being paid “three scudi a month and a horse”, and preparing antidotes for venoms, but also lip balm, for Cosimo I de’ Medici ( Ferdinand’s father) too. Stefano is also quoted as one of the pharmacists making the ultimate and true version of Theriaca: an ancient “omnimorbia poliremedy”, whose name derives from snake’s venom, that has been prescribed for over eighteen centuries as a potent medicine that could cure a number of diseases. The invention of Theriaca is credited to Mitridate, king of Ponto, and perfected by Andromaco the Elder, personal physician to the emperor Nero. Galeno cites 62 ingredients, that became 74 in Spanish pharmacology. In the 16th century the best Theriaca was made in Venice, where eastern ingredients could be added; these included opium, myrrh, cinnamon, gum Arabic, rhubarb, incense, turpentine and more. Stefano made his own version and was called as an expert consultant over the recipe in favour of the scientist and botanist Ulisse Aldrovandi in a famous dispute (they won) against the guild of physicians in Bologna. Going back to Stefano, with the money he made from his business he acquired a villa and planted a garden with all the botanic specimens he both personally collected and obtained through his contacts with the main botanists of the time, including Aldrovandi who is one of the fathers of modern botany. Stefano’s interest was no longer only medical, he became a passionate collector. In the Middle Ages botanical texts, compiled to document plants with medicinal properties( called Semplici), were illustrated with painted images (Horti Pincti). At the beginning of the XIV century botanists found a more reliable method by printing the specimens directly onto the pages (Horti Impressi). This practice lasted for almost two centuries before being substituted by collections of dried specimens ( Horti Sicci ). The most well known example of direct impression of a botanical specimen is a sage leaf found in Leonardo’s Codice Atlantico. Of course Leonardo’s enquiring mind was interested in this practice and he describes how a leaf has to be coated with soot from a candle, laid on paper and rubbed so that it produces an accurate image. Nerofumo ( lampblack) is the medium used for Stefano’s herbarium, while other books were made using inks or paints Stefano’s book is printed on paper with a Fabriano watermark. The first pages are made of a long list of plants copied from the famous herbarium of Andrea Cesalpino. It’s as if the list served as guide to then put together his own collection. The list is annotated in Stefano’s handwriting ( “thorny, grows in edges, diverging leaf but succulent, women call it marmeruce”, “maple whose seeds look like holmoak”). The second part, 83 prints, is the actual collection of prints, made of plants that could be found in Tuscany, both on coastal and mountainous areas and others more exotic that most likely came from his garden.

Some are arranged on the page in a very matter of fact way, some others end up with an interesting composition, some were even overpainted in watercolour. You can imagine my delight at finding out all these facts after having made plants prints, and I had unknowingly decided to use Fabriano paper for editioning them too ! The book doesn’t really have an artistic value, nor it’s a fundamental scientific text, however I find its amateur’s nature very endearing: it really feels like a personal project that was doggedly pursued despite being obsolete ( in 1575 the Horti Sicci were in use, and the codice Rosselli is the last known example of Hortus Impressus). It speaks about Stefano and his passion, and his tiny handwriting ( way smaller than the main copist) in my eyes betrays the seriousness and thoroughness of his character. Another element that filled me with joy is the amount of meaningful exchanges that Stefano has with his correspondents “abroad” (Italy was still divided in different states at the time). A case of an intellectual whose interests take him beyond national borders: he was eager to exchange and share knowledge with foreigners, and although his main interest lies in autochthonous species he wasn’t afraid of “contaminating” his own garden with alien plants that could increase the diversity and potency of his pharmaceutical concoctions.

5 Comments

25/9/2022 05:44:25 pm

This was lovely, thanks for sharing

Reply

Ilaria

25/9/2022 09:33:59 pm

Thank YOU for taking the time to read through it !

Reply

29/1/2023 02:06:29 pm

Excellent article! Thank you for your excellent post, and I look forward to the next one. If you're seeking for discount codes and offers, go to couponplusdeals.com.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Check the list below to see posts on these subjects.Categories

All

AuthorIlaria Rosselli Del Turco is an Italian painter living in London. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed