|

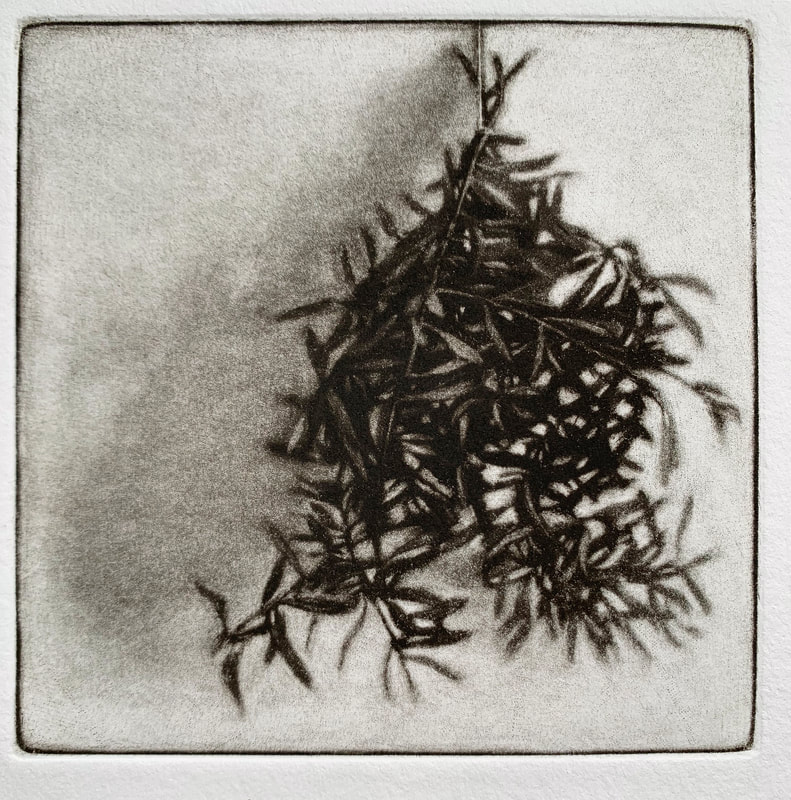

I am very excited to finally share with you a project that I have been working on these past weeks. You might already know how, as a EU citizen, I found the UK political situation of the past three years quite upsetting. As the uncertainty was coming to an unescapable end I set out to make my first artist book as a personal response to events. The book features five of my mezzotint engravings and it's made completely by hand in an edition of 4. Here below is a short video filmed by Alberto Lais. Hortus was conceived as a small Herbarium of Mediterranean plants that I collected on my street. They make the street more beautiful and diverse, and particularly the large olive trees have surprised me for how well they adapted to this colder ( less so now perhaps) climate. The parallel with my own life was obvious and it sparked a series of mezzotint engravings that I titled Immigrant Plants. The idea of collecting these in an artist book came when I learned of a herbarium put together by my ancestor, the pharmacist and botanist Stefano Rosselli, in 1575. I wrote about this extraordinary object here.

I am pretty stubborn and I wanted to make the book on my own, so I set up some sessions with book artist Mark Cockram. He showed me how to bind the pages, set movable types for the letterpress text, and how to make a box, then sent me home to work. The books, an edition of 4 completed on the 31st of January, turned out exactly how I envisioned them !

1 Comment

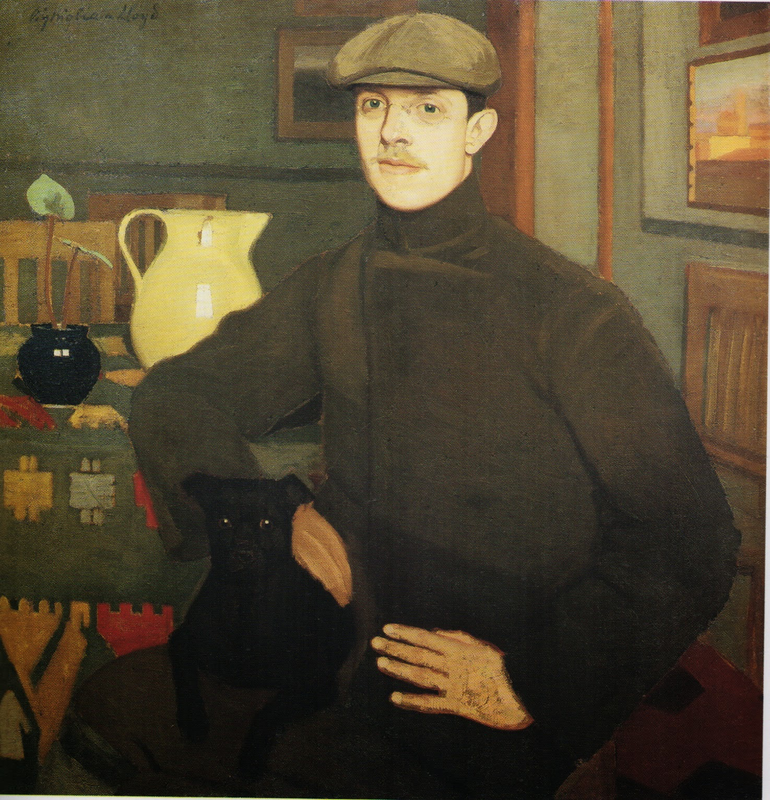

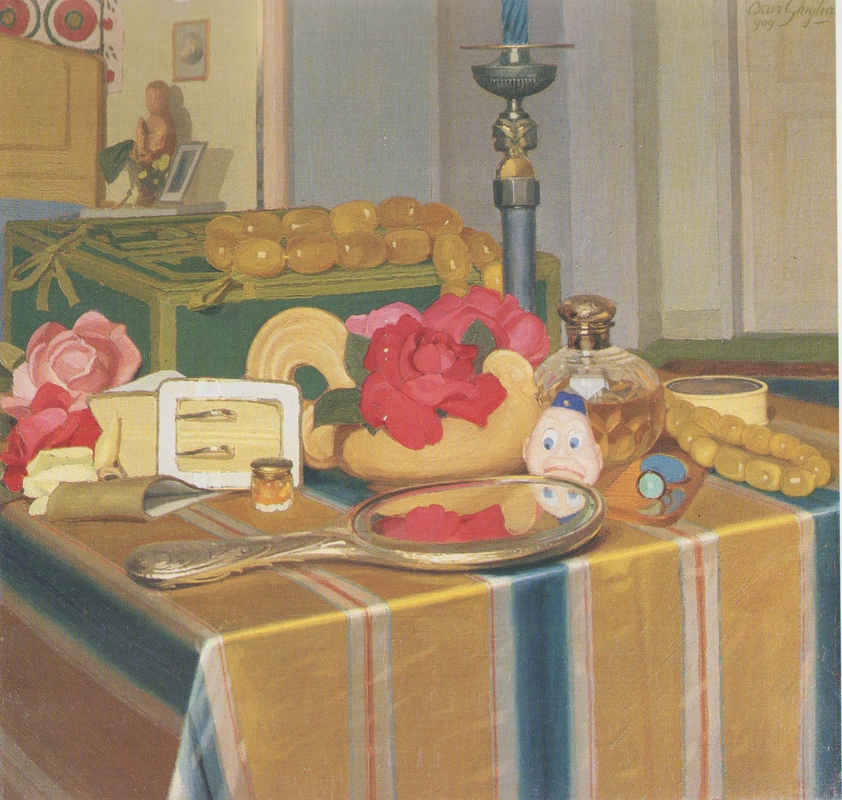

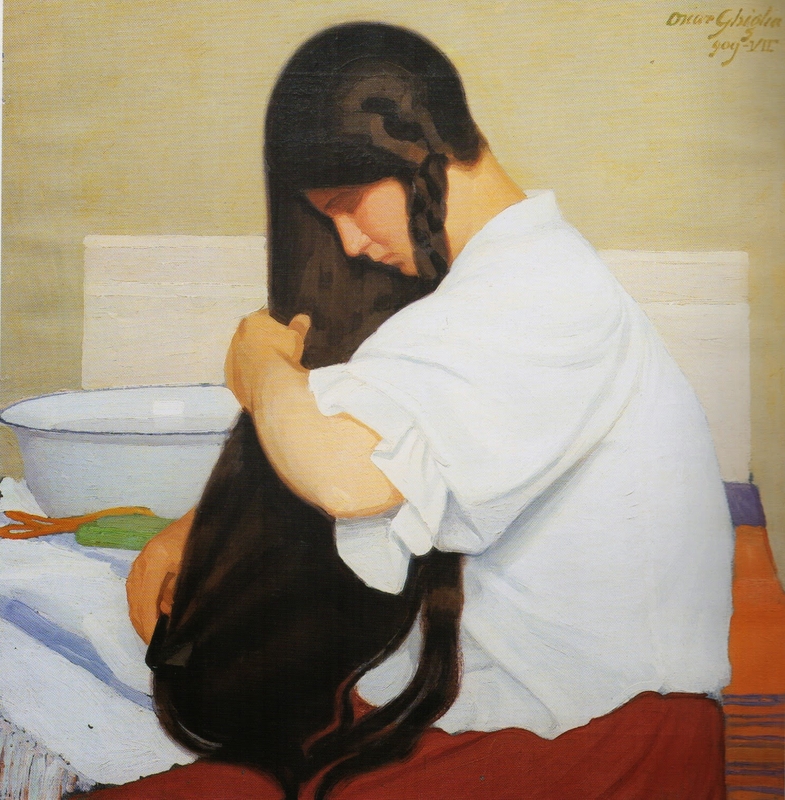

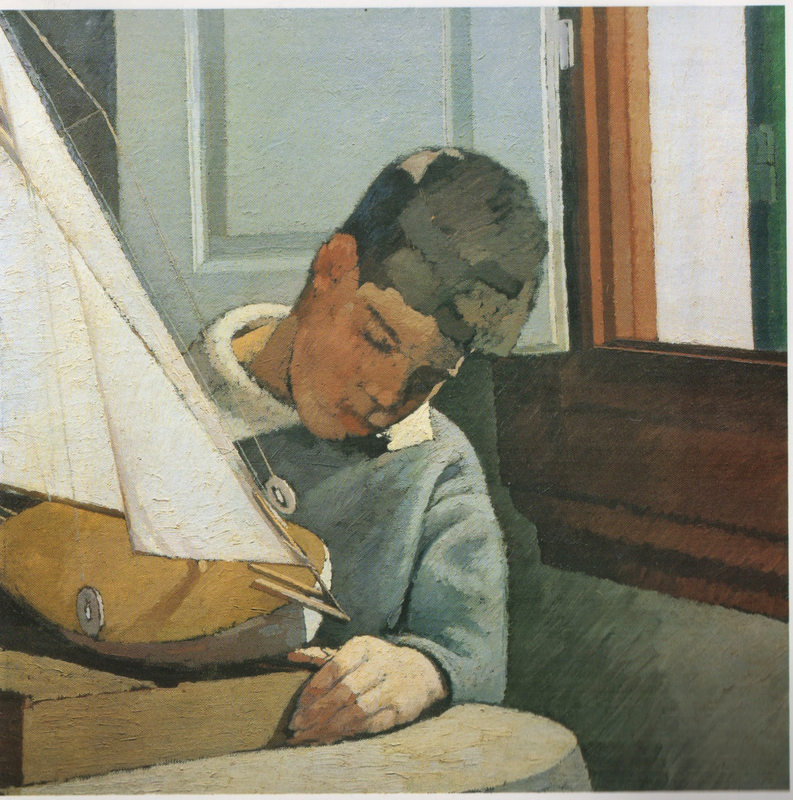

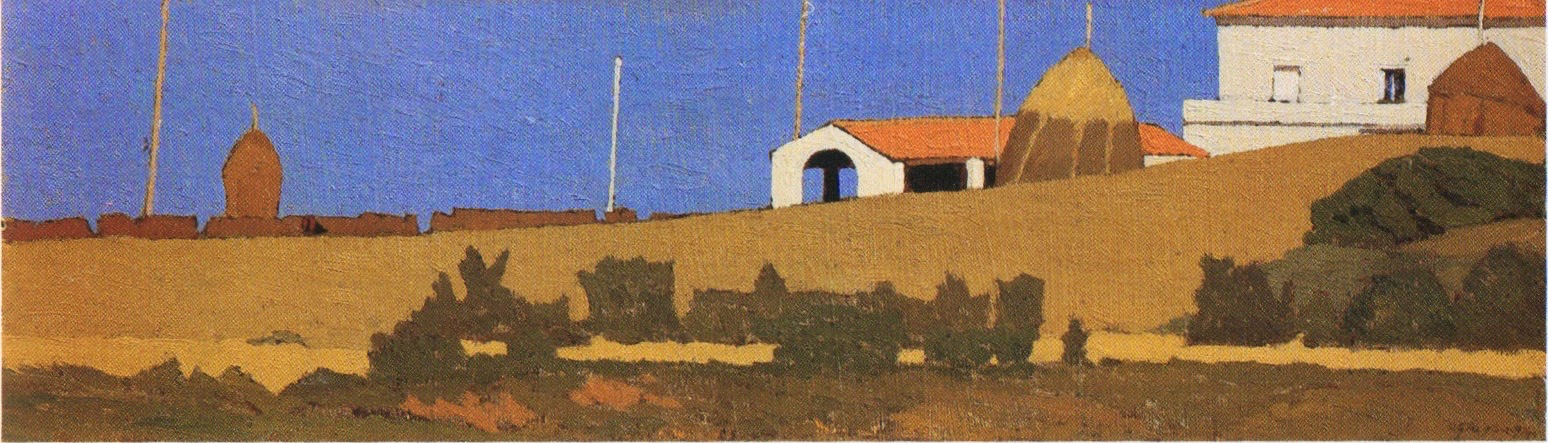

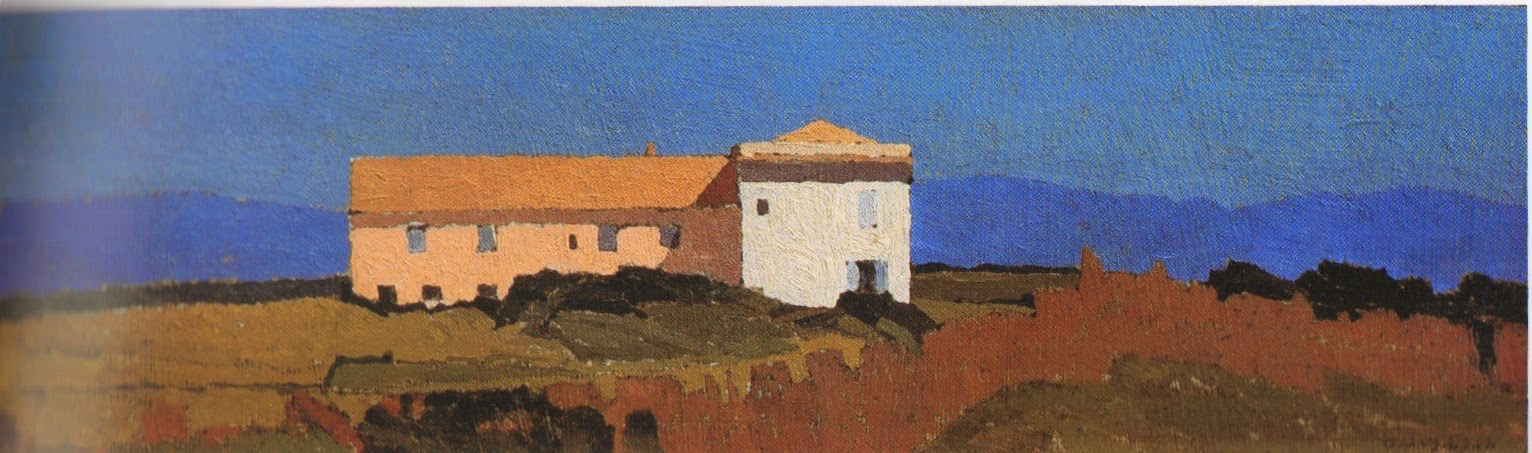

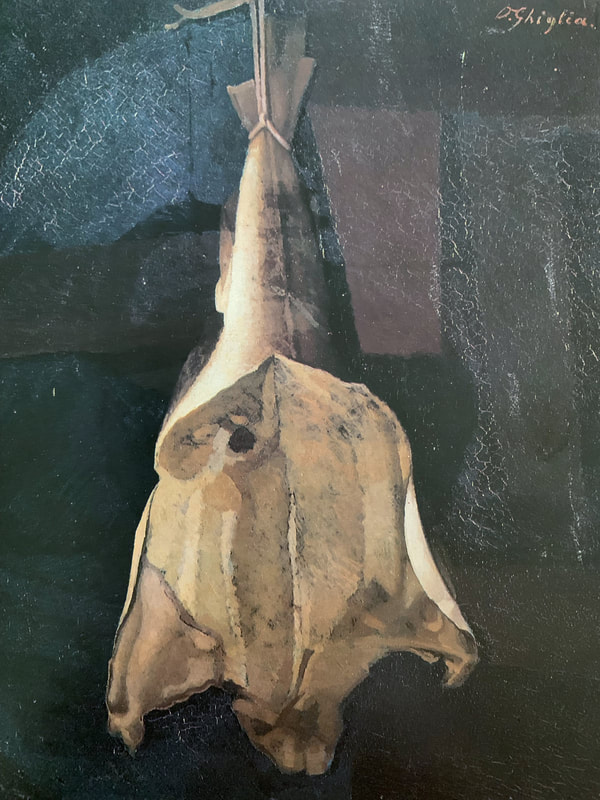

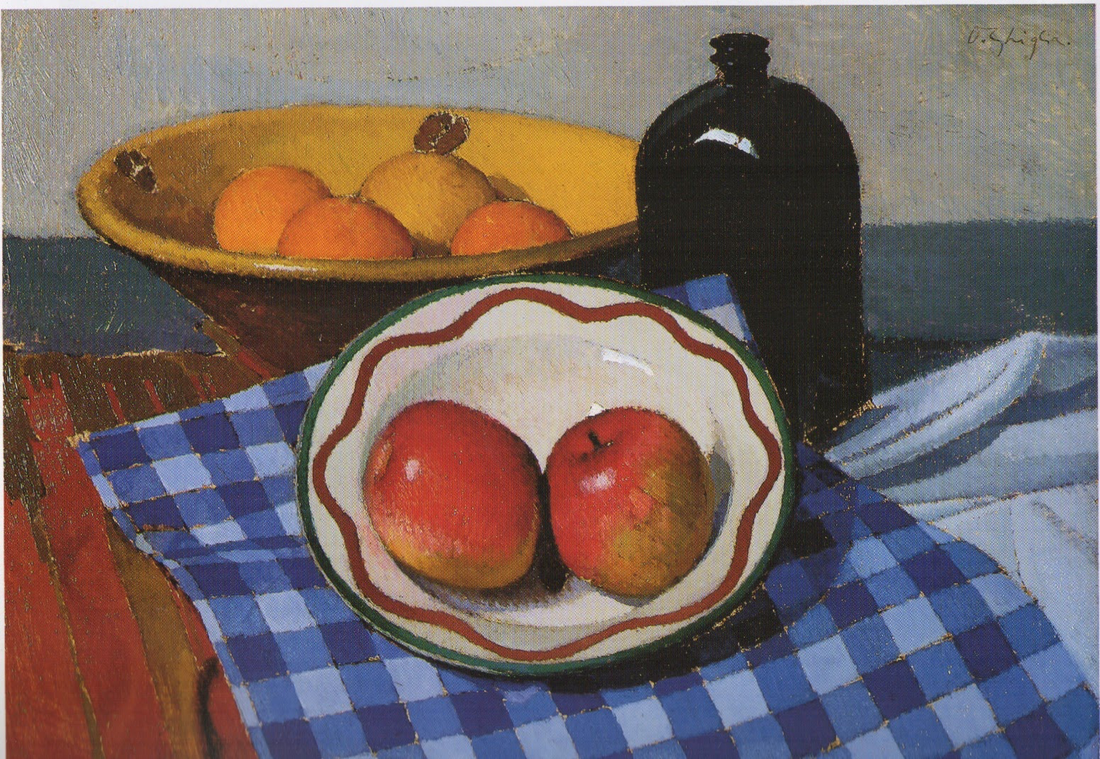

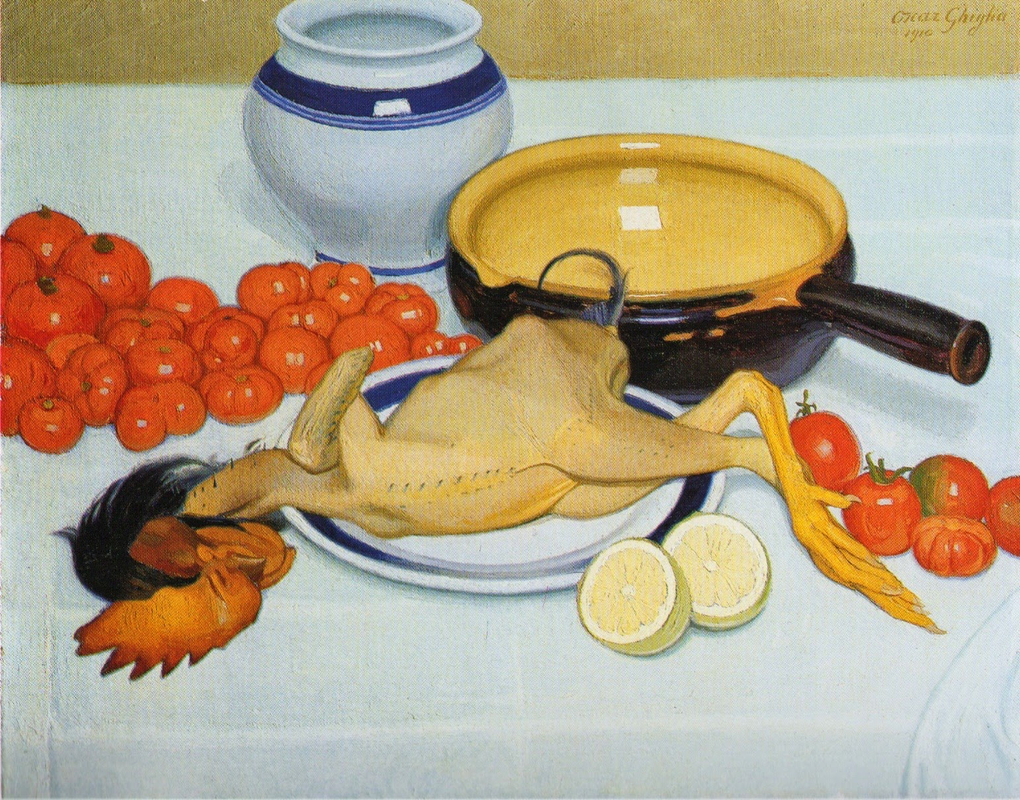

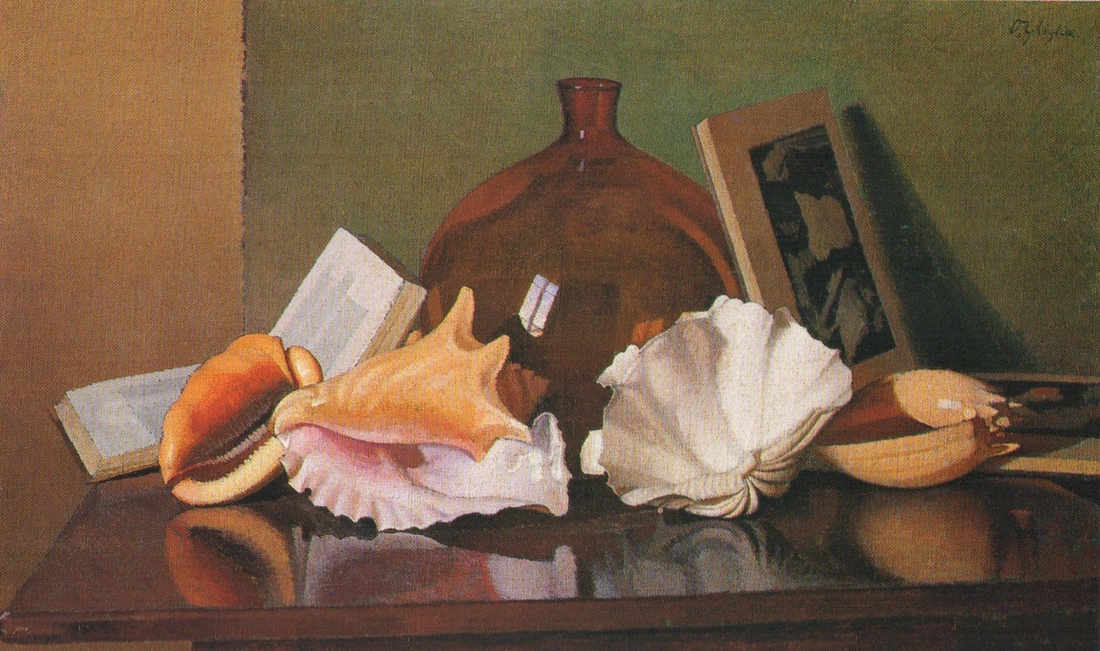

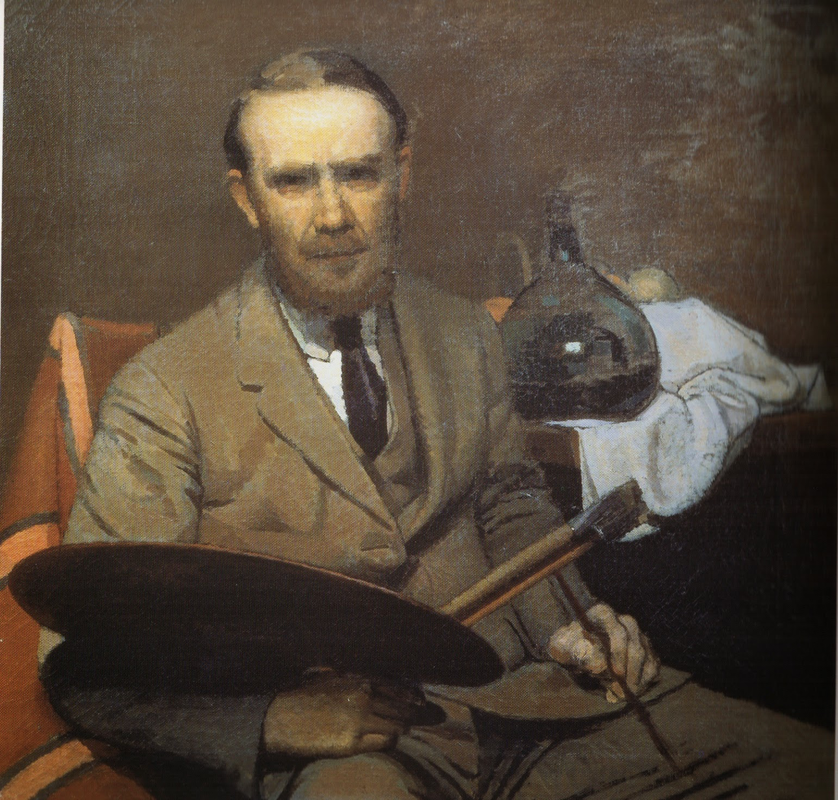

Oscar Ghiglia, A Forgotten Master I came across the work of Oscar Ghiglia in a visit to the museum of Villa Mimbelli in Livorno years ago. Since then I never had enough of looking at his work. Oscar Ghiglia, b.1876, came from a very poor family in Tuscany and lived in poverty for most of his life. He was self taught and started painting in his early youth while doing all sorts of odd jobs. In those years he lived in Livorno, a city on the Tuscan coast. Ghiglia was able to bravely overcome his humble origins and his lack of formal education, and became part of the cultural elite of Tuscany. He wrote that his sordid existance of the first years of his life "is when my character was being delineated, in that I always believed best to communicate with objects than people"- as an explanation for his love of the still life genre. In his youth he befriended the painter Llewellyn Lloyd and Modigliani, who was a little younger and from a very different background. Through Modigliani he came in contact with many jewish families to whom he was close and loyal for the rest of his life, including during the hard years of racial persecution. It was not until 1901 that he moved to Florence and started attending the Scuola del Nudo, led by painter Giovanni Fattori, the star painter of the time. Fattori respected him as an artist and they paid each other studio visits, but Ghiglia did not fully belong to his students' group nor ever ascribed to the divisionist painting language that many Tuscan painter were adopting. In Florence he also joined a group of intellectuals that included Papini and Prezzolini, who will eventually form the core of the Futurists. He was well aware of the social and political situation at the time however his art was deliberately apolitic, and he disliked the -isms of that time. He did not share the fascination for modern machines and speed that was at the core of Futurism, and later on openly condemned fascism and war. Another vital meeting of the end of the century was with his wife Isa: her devotion and affection supported him throughout his life providing the serene atmosphere that is so well depicted in his paintings. Ghiglia's artistic breakthrough happend in 1901 when his self portrait was included in the prestigious Esposizione Universale in Venice. In the meantime he was making real progress, studying the old masters preferring Titian and Rembrandt to the Florentines. His portraits are characterised by a solid perspective structure, immediate but in fact very complex. They never indulge toward sentimentality nor they become flamboyant. With a classical departure point, they are made modern by the simplification of the drawing; all the emotional content is reduced to a precise construction of the image. At the start of his career he mainly painted portraits but in the painting of his friend Lloyd ( above) his interest for still life is starting to appear. In these first years there is no evidence of contacts with European contemporary painting, particularly with artists who had interest in the domestic such as the Nabi or Scandinavian, nor William Nicholson, who were all shown in Venice too. At this stage his development was completely autonomous- although the friendship with Ojetti soon gave him access to the extensive library of this well-known intellectua, and Cezanne's influence can be clearly seen after 1910. In 1914 at the start of WW1 he finds a refuge on the coastal town of Castiglioncello with Isa and their five children. He experiences strong feelings of isolation, as he was seen almost as a bolshevic by the bourgeois holiday makers and far from the warmongering spirit of his frends, the Futurists. Here he will paint some beautiful landscapes that are integral to his work. The format and the subjects recall the Macchiaioli painters but landscape for him is in fact a rational construction. with solid brushwork, the opposite of "optical" impressionism, and an intuition of the surface as the field of chromatic relationships - like a mosaic ( in his own words). In Castiglioncello he will also paint still life and beautiful portraits such as Paulo with the Boat, above. After the war he goes back to Florence, where he witnesses with spite the rise of fascism. Figure comes back into his work, particularly the figure in the mirror, an object that will remain a favourite motif for the next decade. This period sees the resolution of his contract with the collector Gustavo Sforni, who had basically acquired the greatest bulk of his production. It was a relationship that helped him out financially for years but might have ultimately damaged the chances of his paintings circulating more widely. Now in his fifties and increasingly isolated also because of his antifascism, he continued to paint magnificently during the 20s and the 30s. In 1943, while he was an evacuee in the countryside, weakened by sickness, his house, many paintings and all his cast of objects that had appeared in his works were lost in the only allied bombardment of Florence in WW2. Ghiglia died in 1945. Info gathered from: Oscar Ghiglia, Maestro del Novecento Italiano, published by Farsetti Arte in 1996. LISTEN BELOW FOR THE CORRECT PRONOUNCIATION OF HIS NAME

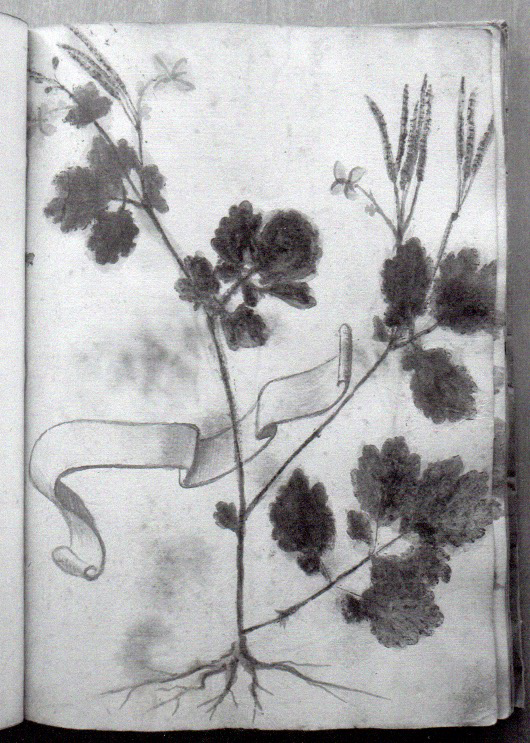

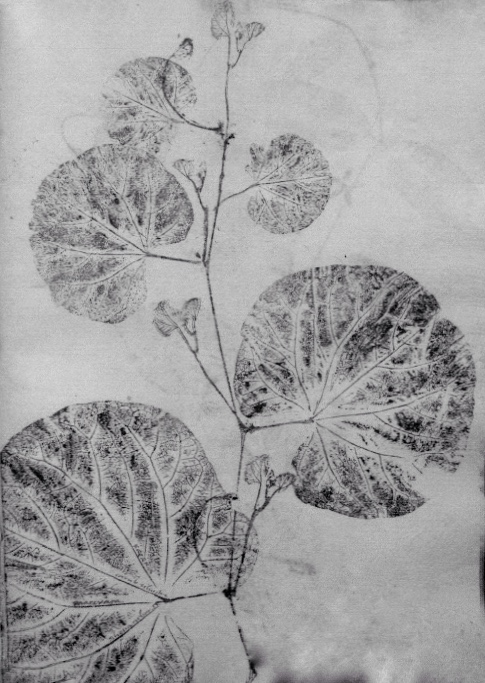

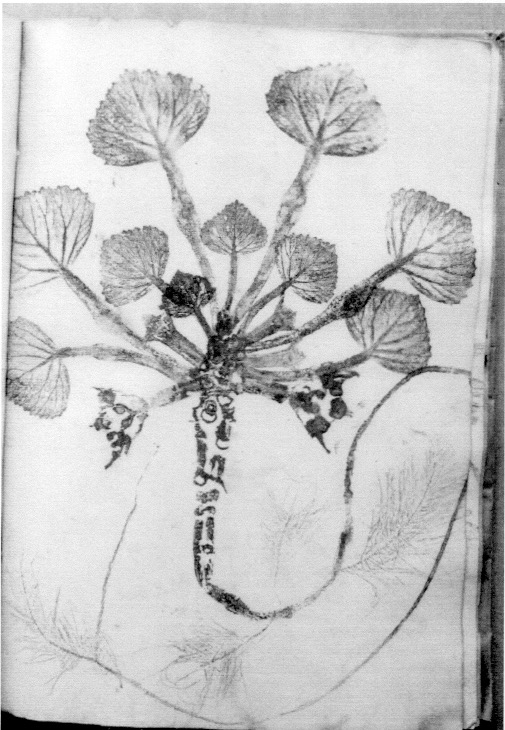

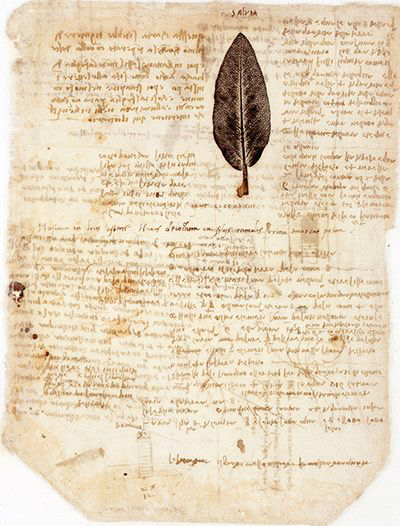

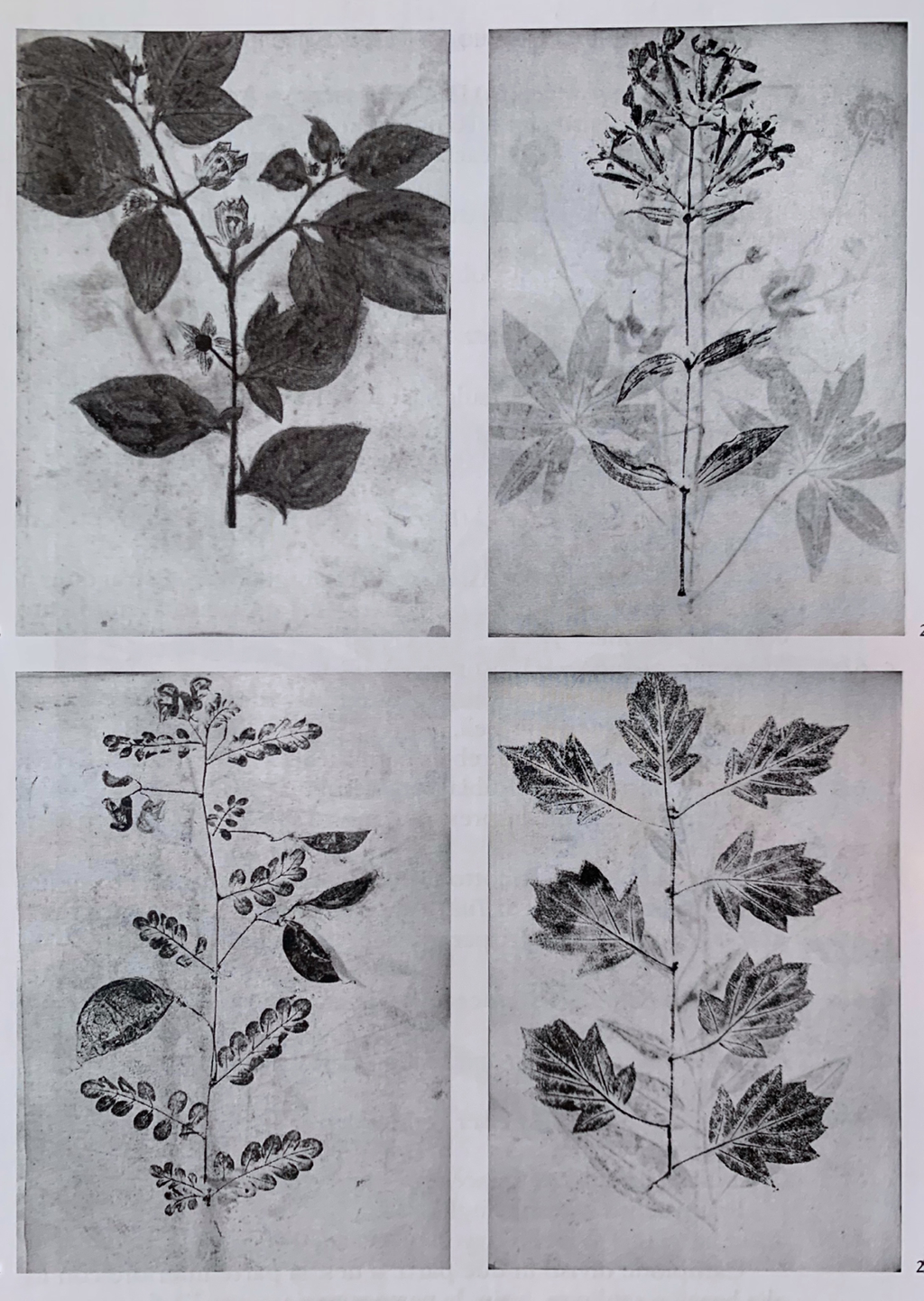

When I embarked in my recent series of mezzotints featuring plants, I didn’t know that I had some sort of precedent in my family. Through a research recently published by a group of academics ( G. Moggi, B. Biagioli, G. Cellai, L. Fantoni, P. Luzzi, C. Nepi) I’ve learned about an ancient book that is in my family’s library in Florence. The book dates from 1575 and is what’s known as Hortus Impressus, a text that presents a collection of plants The book was commissioned and annotated by an ancestor of mine, Stefano Rosselli. He was a “speziale”, basically a pharmacist. He had a flourishing bottega in Florence and his ointments and remedies where so famous that he became the Grand Duke Ferdinand’s pharmacist from 1588 to 1595. There are records of him being paid “three scudi a month and a horse”, and preparing antidotes for venoms, but also lip balm, for Cosimo I de’ Medici ( Ferdinand’s father) too. Stefano is also quoted as one of the pharmacists making the ultimate and true version of Theriaca: an ancient “omnimorbia poliremedy”, whose name derives from snake’s venom, that has been prescribed for over eighteen centuries as a potent medicine that could cure a number of diseases. The invention of Theriaca is credited to Mitridate, king of Ponto, and perfected by Andromaco the Elder, personal physician to the emperor Nero. Galeno cites 62 ingredients, that became 74 in Spanish pharmacology. In the 16th century the best Theriaca was made in Venice, where eastern ingredients could be added; these included opium, myrrh, cinnamon, gum Arabic, rhubarb, incense, turpentine and more. Stefano made his own version and was called as an expert consultant over the recipe in favour of the scientist and botanist Ulisse Aldrovandi in a famous dispute (they won) against the guild of physicians in Bologna. Going back to Stefano, with the money he made from his business he acquired a villa and planted a garden with all the botanic specimens he both personally collected and obtained through his contacts with the main botanists of the time, including Aldrovandi who is one of the fathers of modern botany. Stefano’s interest was no longer only medical, he became a passionate collector. In the Middle Ages botanical texts, compiled to document plants with medicinal properties( called Semplici), were illustrated with painted images (Horti Pincti). At the beginning of the XIV century botanists found a more reliable method by printing the specimens directly onto the pages (Horti Impressi). This practice lasted for almost two centuries before being substituted by collections of dried specimens ( Horti Sicci ). The most well known example of direct impression of a botanical specimen is a sage leaf found in Leonardo’s Codice Atlantico. Of course Leonardo’s enquiring mind was interested in this practice and he describes how a leaf has to be coated with soot from a candle, laid on paper and rubbed so that it produces an accurate image. Nerofumo ( lampblack) is the medium used for Stefano’s herbarium, while other books were made using inks or paints Stefano’s book is printed on paper with a Fabriano watermark. The first pages are made of a long list of plants copied from the famous herbarium of Andrea Cesalpino. It’s as if the list served as guide to then put together his own collection. The list is annotated in Stefano’s handwriting ( “thorny, grows in edges, diverging leaf but succulent, women call it marmeruce”, “maple whose seeds look like holmoak”). The second part, 83 prints, is the actual collection of prints, made of plants that could be found in Tuscany, both on coastal and mountainous areas and others more exotic that most likely came from his garden.

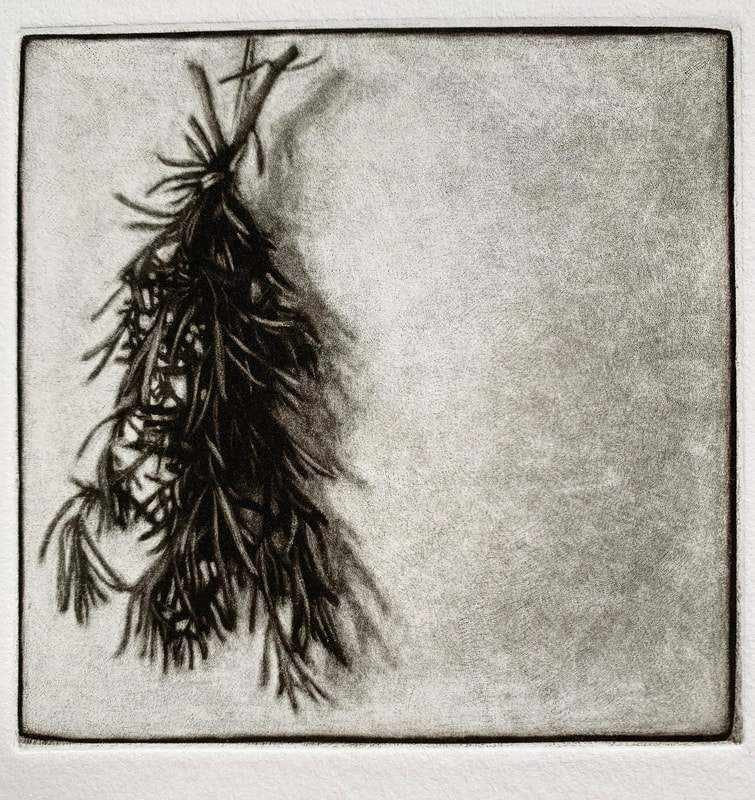

Some are arranged on the page in a very matter of fact way, some others end up with an interesting composition, some were even overpainted in watercolour. You can imagine my delight at finding out all these facts after having made plants prints, and I had unknowingly decided to use Fabriano paper for editioning them too ! The book doesn’t really have an artistic value, nor it’s a fundamental scientific text, however I find its amateur’s nature very endearing: it really feels like a personal project that was doggedly pursued despite being obsolete ( in 1575 the Horti Sicci were in use, and the codice Rosselli is the last known example of Hortus Impressus). It speaks about Stefano and his passion, and his tiny handwriting ( way smaller than the main copist) in my eyes betrays the seriousness and thoroughness of his character. Another element that filled me with joy is the amount of meaningful exchanges that Stefano has with his correspondents “abroad” (Italy was still divided in different states at the time). A case of an intellectual whose interests take him beyond national borders: he was eager to exchange and share knowledge with foreigners, and although his main interest lies in autochthonous species he wasn’t afraid of “contaminating” his own garden with alien plants that could increase the diversity and potency of his pharmaceutical concoctions. I've never been a political artist, however since my works are very personal it was inescapable that some current affairs were going to seep in. Here's a bit about me: I moved to London from Italy twenty years ago when my husband was relocated here - it wasn't a choice and honestly with three kids under five and having already moved three times in the previous five years I would have happily stayed where I was, but my reluctance was soon forgotten and my London life started. I definetely belong to the Easyjet generation, we live in a different nation from our family and old friends but then they are just a short flight away, we keep in touch easily, we can chat about the same TV shows, keep track of our holidays on Instagram. The word emigrant somehow sounds too extreme for me, it reminds me of people who settle far away from home and start a new life. My life is not too different from that one of my friends in Italy and I plan to go back at some point, I am probably more of a "semigrant", one foot here and one there, like many EU citizens I felt that the concept of home can be stretched by a couple of thousands kilometers. And then, here comes Brexit. During the campaign immigration was a big issue: EU citizens are evaluated for their contribution. Leave politicians paint us as a burden to UK society, Remainers advocate for us because we are workers, tax payers, consumers. All of a sudden I need a valid reason to live in Britain. I never thought of myself like that, reduced to productivity terms, I find it very sad. I believe that the benefits of freedom of movement in Europe go beyond the - well proven - economic advantages; they enrich our knowledge and further social progress, make us more rounded and empathic human beings without losing an ounce from our respective national identity. Through the past three years in my studio I tried to shut out this noise, but I wonder if my paintings have become darker, murky, and more doubtful. This past year my still life have included more plants, such as this painting of oleander leaves that I cut from a shrub I planted years ago at my front door. I had an idea for a mezzotint, using the same leaves for a simple composition in a square. It was during the long hours spent on that copper plate that I asked myself about the oleander. I planted it, it's personal. But why did I plant an oleander ? I remember just picking what I was familiar with. Oleanders are everywhere in Italy, and Italian kids are always warned not to touch them because they are poisonous. I also remember that I doubted it would survive English climate but surprisingly those few twigs grew to a very large shrub, they thrived here. Like myself, I thought. I immediately decided to start a series that I have titled Immigrant Plants, featuring mediterranean plants that I watched growing in u neighbourhood. I stole some olive branches from a tree that was inexplicably planted round the corner about fifteen years ago, an extravagant choice for urban decoration. The spindly sapling now has a magnificent twisted trunk. The rosemary is from my front garden again, where it bravely resists my carelessness. Some Bay leaves are in the works.  Immigrant Plants - Ulivo ( Mezzotint 12.5x12.5 cm) Immigrant Plants - Ulivo ( Mezzotint 12.5x12.5 cm) I miss the time when news weren't monopolised by the fruitless discussions about trade and rules. I hope to hear more voices that advocate for freedom of movement and for the merits of a diverse and multinational society and for the principles of cooperation and solidarity.

If there's one thing I have to force myself to do is going to the gym. I know it's good for me blah blah but I find it utterly boring and I am so good at procrastinating that my morning session always happens around 7pm. Because of the random nature of studio days I don't go to classes, I rather do my thing and that's when listening to some engaging conversation has the magic power of keeping me on a tedious rowing machine beyond my first sweat. Enter the arty podcast, an audio program that is just long enough to last one gym session ( or a good walk). I like listening to podcasts when I am not in the studio, as some of them are so interesting that they distract me from painting, but some times while I work I listen again to the ones that I found more inspiring or motivating to see if they generate ideas or throw new light on the painting I am working on. I originally drafted this list for my old blog in 2015 and it is lovely that many are still going ! Here's my updated list : PAINTERS TALKING ABOUT PAINTING - Studio Break It's a new find for me, I got there following the guys from Printeresting, a printmaking blog, and had a look around to find two interviews with FB friend Joe Morzuch so started listening. The interviewer, artist David Linneweh is very good at conducting the conversation and asks the same questions I would ask. Update 2018: I since have been interviewed by David ! -Savvy Painter Features artists in conversation with painter artist Antrese Wood. She touches on practical aspects of painting such as promoting the work, as well as asking interviewees about their career path or their daily studio practice. Artists that have been interviewed include Israel Hershberg, James Bland, Stuart Shils, Mitchell Johnson, Stanka Kordic, Karen Kaapke, Dean Fisher and many others. -John Dalton Gently Does It John is another very good interviewer. His podcass feature many well known painters and are quite long so they go deeper into the conversation. John has also started a subscriber page on Patreon, asking for just a dollar a month to sustain the podcast: an easy way to donate. -Suggested Donation Generally focussed on classically trained artists, Only six women interviewees in more than forty episodes ! - Art Grind Podcast Long conversations among artists conducted in person by three interviewers, very nice atmosphere and interesting considerations. -Artist Decoded Host Yoshino interviews a variety of artists, not only painters. Urban feel. - The Studio- Interviewer Danny Grant also focusses mainly on classically trained painters. MARKETING FOR ARTISTS - Artists Helping Artists. Lots of tips to navigate social networks, ideas and tricks to be well organised in the studio, useful apps and more. ART HISTORY AND EXHIBITIONS National Gallery of Art (US) Great collection of lectures recordings from the NGA education programs. The Modern Art Notes Podcast Thoughtful interviews with artists, curators, art historians and authors Getty Art + Ideas A variety of interviewees often linked with current exhibitions at the Getty Museum. NO LONGER UPDATED BUT STILL AVAILABLE - The Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center Features a variety of artists in conversation with the art critic Peter Trippi. Includes artists such as William Bailey, Lois Dodd, Gillian Pederson Krag and my friend Alexandra Tyng. - The Royal Academy Features academic introductions to shows by curators or artists, interviews and conversations. The recent conversation between Tim Marlow and Frank Auerbach is probably THE perfect podcast. I hope you like my selection. Alternatively here's some cardio class entartainment: |

Check the list below to see posts on these subjects.Categories

All

AuthorIlaria Rosselli Del Turco is an Italian painter living in London. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed