|

I am very excited to finally share with you a project that I have been working on these past weeks. You might already know how, as a EU citizen, I found the UK political situation of the past three years quite upsetting. As the uncertainty was coming to an unescapable end I set out to make my first artist book as a personal response to events. The book features five of my mezzotint engravings and it's made completely by hand in an edition of 4. Here below is a short video filmed by Alberto Lais. Hortus was conceived as a small Herbarium of Mediterranean plants that I collected on my street. They make the street more beautiful and diverse, and particularly the large olive trees have surprised me for how well they adapted to this colder ( less so now perhaps) climate. The parallel with my own life was obvious and it sparked a series of mezzotint engravings that I titled Immigrant Plants. The idea of collecting these in an artist book came when I learned of a herbarium put together by my ancestor, the pharmacist and botanist Stefano Rosselli, in 1575. I wrote about this extraordinary object here.

I am pretty stubborn and I wanted to make the book on my own, so I set up some sessions with book artist Mark Cockram. He showed me how to bind the pages, set movable types for the letterpress text, and how to make a box, then sent me home to work. The books, an edition of 4 completed on the 31st of January, turned out exactly how I envisioned them !

1 Comment

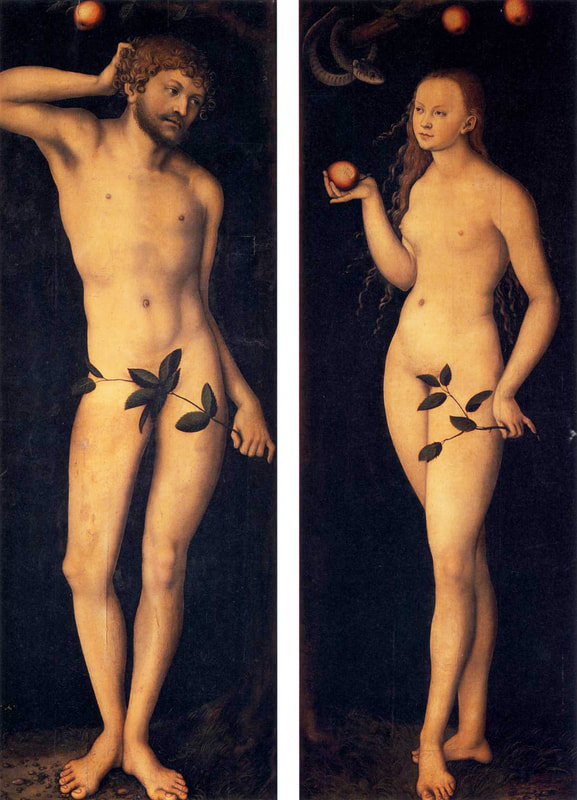

A few years ago he published a very entertaining and pleasant book, Il Museo Immaginato, where he plays at designing an ideal museum where he can hang any work of art. The virtual institution about which he fantasizes in the book, that would be designed like a house and include a kitchen ( with works by Zurbaran, Cotan, Campi, Rembrandt ), a cellar ( Velasquez, who else?), a dining room with paintings by Veronese, and so on. Do you want to appear as scholarly snob as Mr Daverio in his trademark bowtie? Clearly indicate your belonging to continental culture ? Here are some expressions I picked up in the book that you can carelessly drop in your arty conversation: HANCHEMENT ( or Contrapposto): the body posture of classic sculpture where the weight is supported by one leg ( Standbein, let's throw in some German too) while the other (Spielbein) is relaxed. Useful also to describe Cranach's postures. DRANG NACHT SÜDEN: it's the pull towards the South. Barbaric hordes felt the call to cross the Alps, and Goethe of course, but why not apply it to all the Gran Tourists and to the northerners dwelling in the Riviera, such as Matisse ? VERGISSEMEINNICHT: what? Do you call this humble blue flower from Durer's Adoration forget-me-not ? Then you wouldn't be referencing its importance in medieval German culture as a symbol of enduring love and, later, freemasonry. MENUS PLAISIRS : No, this is not found in restaurants, it's the part of a royal household that would have organised events and celebrations. The aristocratic personality responsible for the Menus Plaisirs was in charge, for example, of the design of porcelains or ephemeral decorations, fireworks and music. NICCHIO: that's a scallop, but not in its edible form. The Coquille Saint Jaques was the symbol of Saint James, it's were Botticelli's Venus stands and is seen in many architectural niches ( hence the name) both painted in trompe l'oeil or sculpted. Piero della Francesca has genially reversed it in his Pala di Brera and made it into a striking element from which an ostrich egg ( an animal that at the time thought of as hermaphrodite, so self-fecundating) is hanging. WUNDERKAMMER: of course you already know about this cabinet of wonders that was the favourite guilty pleasures of princes and dukes all over Europe. Who was the trend-setter? It was the typically prognathous Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II , who had withdrawn to his castle in Prague and was curing his melancholy with compulsive collectionism. FLOHPELTZ: It's that soft and luxurious fur worn by Parmigianino's young girl and many other painted ladies. It was used to attract lice and fleas away from the body and head. I confess I might have a jacket with a fur collar... seems much less nice now. ACCROCHAGE: You are not really still calling it the museum's "display", are you?

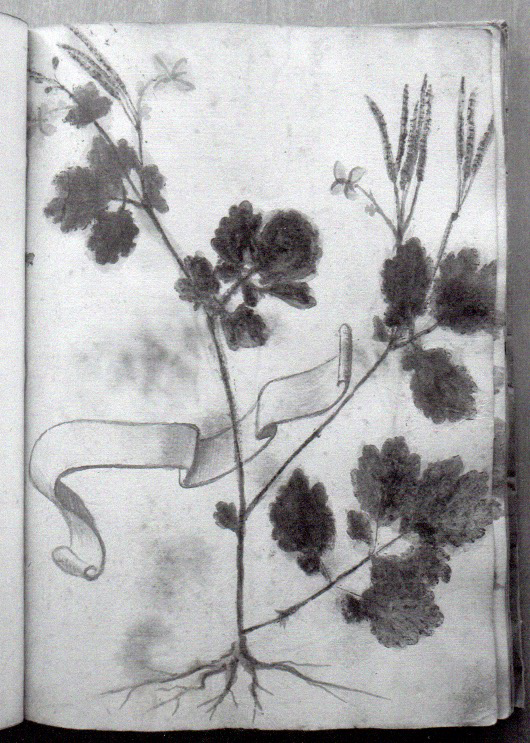

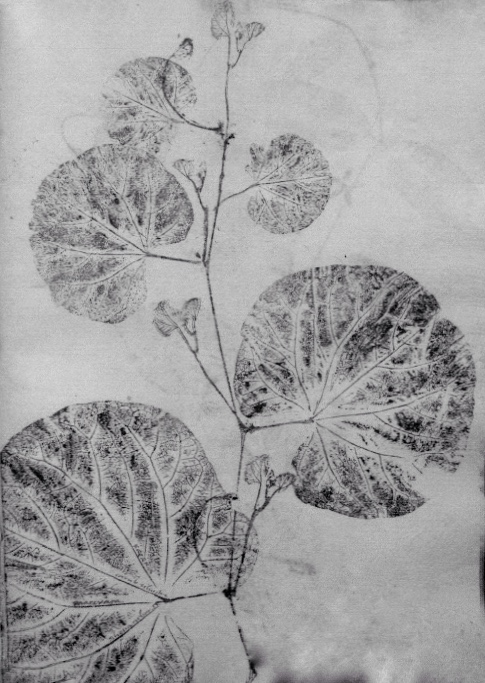

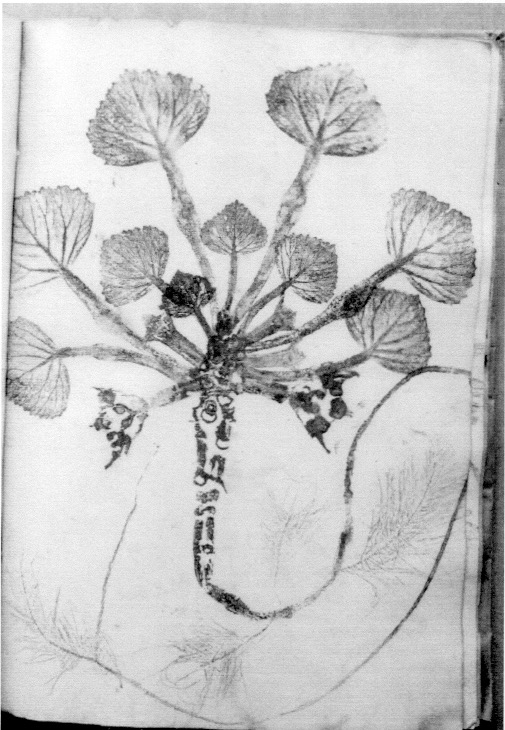

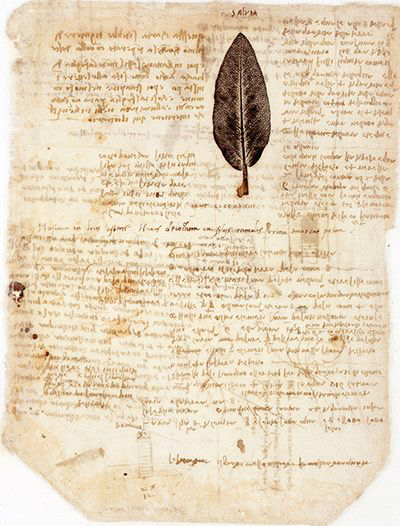

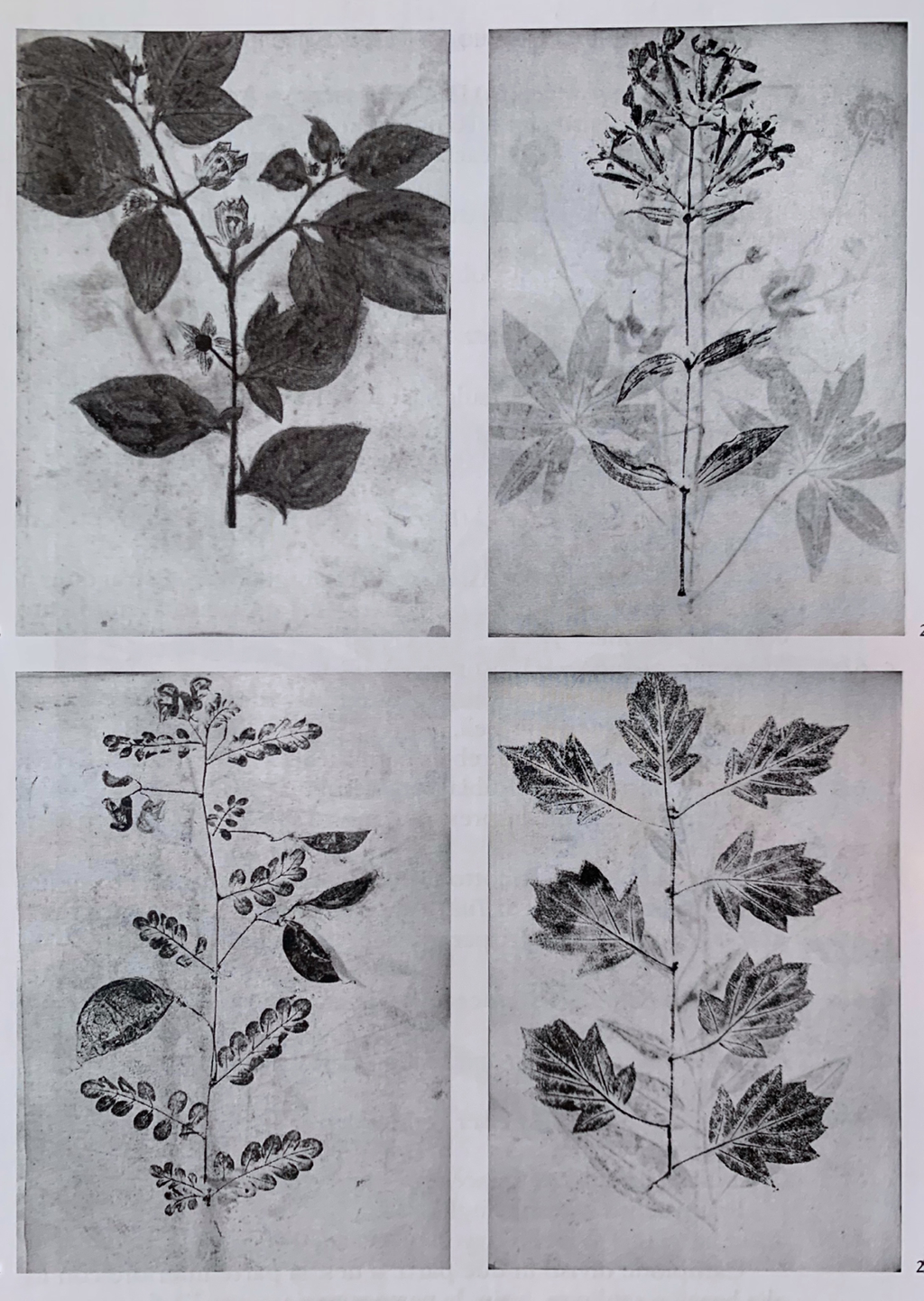

DAS LAND WO DIE ZITRONEN BLÜHN: Goethe again, speaking about Italy, the land where lemons bloom. Stick some French in your sentences and you are sophisticated, but try German and you'll be... übercool When I embarked in my recent series of mezzotints featuring plants, I didn’t know that I had some sort of precedent in my family. Through a research recently published by a group of academics ( G. Moggi, B. Biagioli, G. Cellai, L. Fantoni, P. Luzzi, C. Nepi) I’ve learned about an ancient book that is in my family’s library in Florence. The book dates from 1575 and is what’s known as Hortus Impressus, a text that presents a collection of plants The book was commissioned and annotated by an ancestor of mine, Stefano Rosselli. He was a “speziale”, basically a pharmacist. He had a flourishing bottega in Florence and his ointments and remedies where so famous that he became the Grand Duke Ferdinand’s pharmacist from 1588 to 1595. There are records of him being paid “three scudi a month and a horse”, and preparing antidotes for venoms, but also lip balm, for Cosimo I de’ Medici ( Ferdinand’s father) too. Stefano is also quoted as one of the pharmacists making the ultimate and true version of Theriaca: an ancient “omnimorbia poliremedy”, whose name derives from snake’s venom, that has been prescribed for over eighteen centuries as a potent medicine that could cure a number of diseases. The invention of Theriaca is credited to Mitridate, king of Ponto, and perfected by Andromaco the Elder, personal physician to the emperor Nero. Galeno cites 62 ingredients, that became 74 in Spanish pharmacology. In the 16th century the best Theriaca was made in Venice, where eastern ingredients could be added; these included opium, myrrh, cinnamon, gum Arabic, rhubarb, incense, turpentine and more. Stefano made his own version and was called as an expert consultant over the recipe in favour of the scientist and botanist Ulisse Aldrovandi in a famous dispute (they won) against the guild of physicians in Bologna. Going back to Stefano, with the money he made from his business he acquired a villa and planted a garden with all the botanic specimens he both personally collected and obtained through his contacts with the main botanists of the time, including Aldrovandi who is one of the fathers of modern botany. Stefano’s interest was no longer only medical, he became a passionate collector. In the Middle Ages botanical texts, compiled to document plants with medicinal properties( called Semplici), were illustrated with painted images (Horti Pincti). At the beginning of the XIV century botanists found a more reliable method by printing the specimens directly onto the pages (Horti Impressi). This practice lasted for almost two centuries before being substituted by collections of dried specimens ( Horti Sicci ). The most well known example of direct impression of a botanical specimen is a sage leaf found in Leonardo’s Codice Atlantico. Of course Leonardo’s enquiring mind was interested in this practice and he describes how a leaf has to be coated with soot from a candle, laid on paper and rubbed so that it produces an accurate image. Nerofumo ( lampblack) is the medium used for Stefano’s herbarium, while other books were made using inks or paints Stefano’s book is printed on paper with a Fabriano watermark. The first pages are made of a long list of plants copied from the famous herbarium of Andrea Cesalpino. It’s as if the list served as guide to then put together his own collection. The list is annotated in Stefano’s handwriting ( “thorny, grows in edges, diverging leaf but succulent, women call it marmeruce”, “maple whose seeds look like holmoak”). The second part, 83 prints, is the actual collection of prints, made of plants that could be found in Tuscany, both on coastal and mountainous areas and others more exotic that most likely came from his garden.

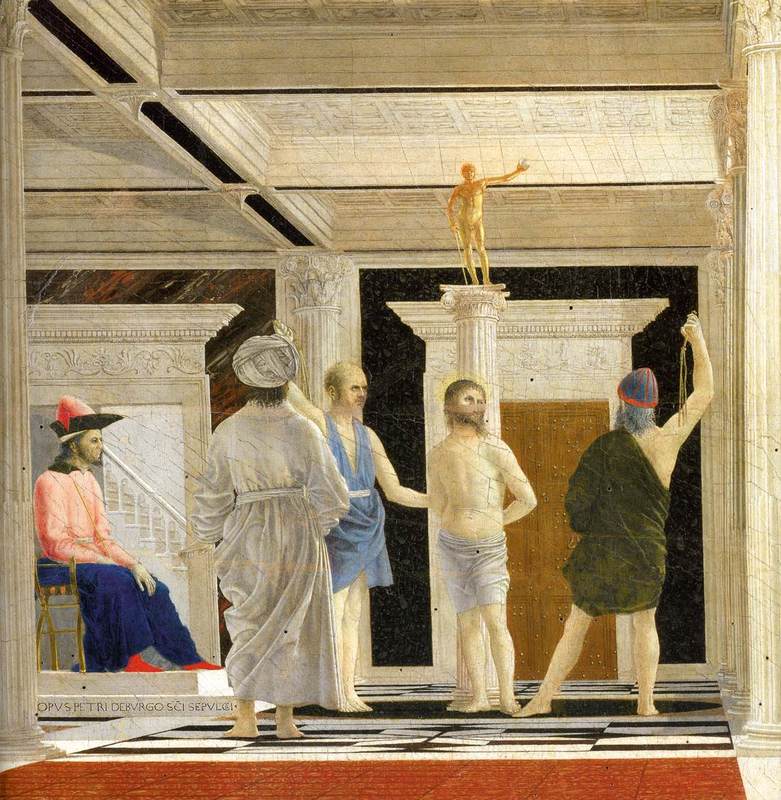

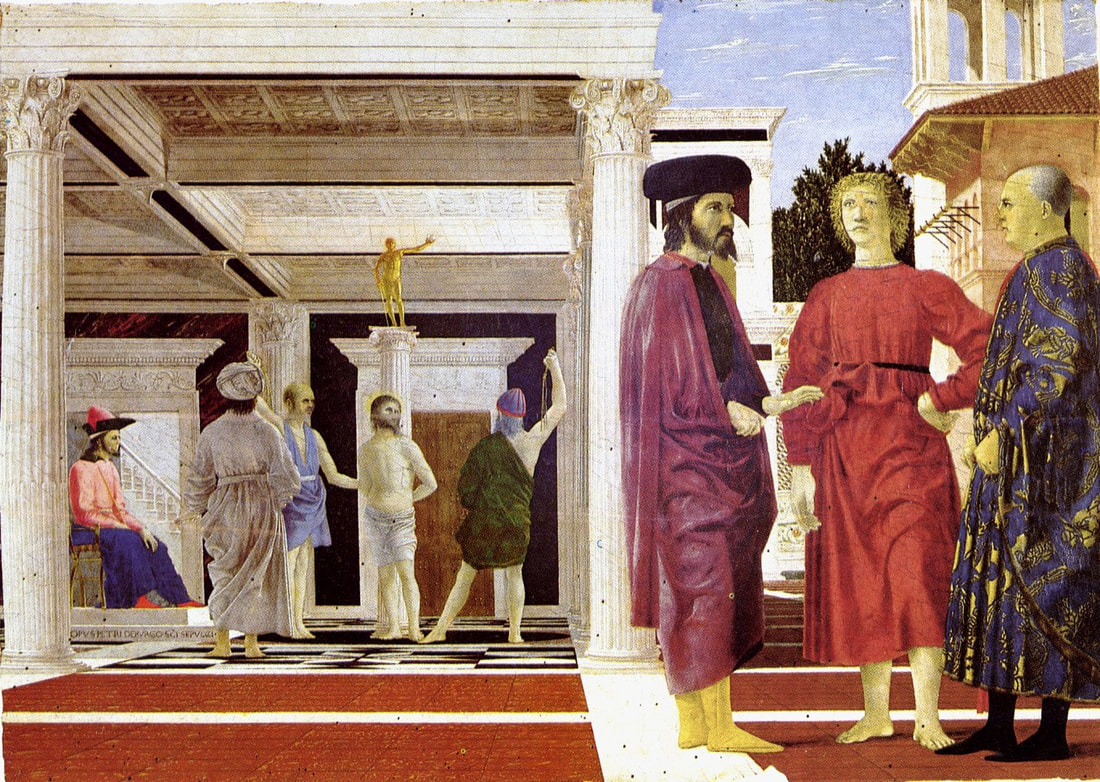

Some are arranged on the page in a very matter of fact way, some others end up with an interesting composition, some were even overpainted in watercolour. You can imagine my delight at finding out all these facts after having made plants prints, and I had unknowingly decided to use Fabriano paper for editioning them too ! The book doesn’t really have an artistic value, nor it’s a fundamental scientific text, however I find its amateur’s nature very endearing: it really feels like a personal project that was doggedly pursued despite being obsolete ( in 1575 the Horti Sicci were in use, and the codice Rosselli is the last known example of Hortus Impressus). It speaks about Stefano and his passion, and his tiny handwriting ( way smaller than the main copist) in my eyes betrays the seriousness and thoroughness of his character. Another element that filled me with joy is the amount of meaningful exchanges that Stefano has with his correspondents “abroad” (Italy was still divided in different states at the time). A case of an intellectual whose interests take him beyond national borders: he was eager to exchange and share knowledge with foreigners, and although his main interest lies in autochthonous species he wasn’t afraid of “contaminating” his own garden with alien plants that could increase the diversity and potency of his pharmaceutical concoctions. ( Read Part One Here) So, who are these mysterious characters that populate the painting ? The argument has been going on for decades, and Ronchey adds her theory while at the same time mentioning past interpretations and explaining why she agrees or not with them The first key to understanding the painting is to try and put a date on its execution. This is another element that has been controversial. Ronchey agrees with many in placing it around 1458-1459 mainly because of the influences of Leon Battista Alberti's architectures that are echoed in the painting. This means Piero has ultimated the Flagellation just before the Council of Mantova, the one in which Bessarion and Pope Pius II were trying to find funds and members for the crusade. In Ronchey exegesis the work does not refer to the Council of Mantova, though, but to the previous attempt at saving Bysantium, the Council of Ferrara/Firenze ( it had moved from one city to the other because of the threat of a plague epidemic). The procession of hundreds of Byzantine personalities with their colourful clothes and strange hats was seen by a huge crowd, among which probably Piero. The artist who we know got to get a privileged view of the dignitaries and of the Basileus ( then Giovanni VIII Paleologo) in person was Pisanello. There is a large group of drawings by Pisanello ( Louvre) where he had sketched people and costumes. Pisanello also was the author of at least one medal, bearing the profile image of the Basileus, that had a wide circulation and became his definitive portrait in those years. So we can affirm that the first figure in the Praetorium is Giovanni VIII Paleologo, who is pictured as Pontius Pilatus, and is wearing the red footwear that were the attribute of the Basileus. Giovanni, argues Ronchey, is not the one who is letting the flagellation happen ( this is a more contemporary view of the gospel's figure), but rather a powerless witness to it. The person who is responsible for ordering the flagellation is actually the figure standing barefooted with our back to us. He is identified with the Sultan Mehmet II, the conqueror of Costantinople. After the occupation of the town Mehmet had his men look for the body of the dead Emperor: He was after the red footwear embroidered with the double-headed black eagle, symbol of imperial power. That is why he is now pictured without footwear ( at the time of the Council of Mantua Constantinople had yet not fallen). The two men performing the flagellation seem to be two pirates of which there's an iconographic precedent again in Pisanello's drawings. The body of Christ represents symbolically the church of Bysantium. He is tied to a column on top of which is a golden sculpture that might be identified with the huge bronze statue of Emperor Costantino, of which only a few fragments now remain, that was in Rome in front of the Lateran. The whole space in fact represents the town of Constantinople. In this vision, the two spaces in which the painting is divided are not removed in time from one another, but in space. What happens to the left of the painting, the torture of Constantinople, picture symbolically as the flagellation of Christ, is happening WHILE the three figures on the right are discussing the situation. As we have seen the painting refers to the Council of Ferrara-Firenze. The first figure on the left, the greek mediator, is identified by Ronchey with Bessarione. We don't have any confirmed image of the Cardinal at a younger age, but the double pointed beard, the cloak and hat all point to the charismatic Cardinal. Elements of the architecture in the right hand side are another sign that point at the Council of Ferrara. The roof on the left is found in a painting by Francesco del Cossa and reference the tower by Leon Battista Alberti. There is only one last figure to identify, the striking young man dressed in crimson that echos the posture of the tortured Christ. "Porfirogenito", this was what the basileus was called, "he who was born in porpora ( crimson, the imperial colour). The man looks like other figures painted by Piero: a fragment of a fresco in Sansepolcro, an angel in the National Gallery Baptism, a prophet in the fresco from the Duomo of Arezzo. Ronchey argues that this is an idealised portrait of Tommaso Paleologo, the youngest brother of the Emperor who could inherit the throne if it was to be saved. A bearded Tommaso, twenty years older but still fair and " of great aspect", would arrive in Italy for his melancholic exile, where he would die as ever assisted by Bessarione in 1465. In 1474 the Cardinal was still looking for help for the Empire. Tommaso's daughter Zoe was the csarina of Russia, and Bessarione left for France and England to try and organise yet another crusade. He knew his health was declining and he had planned to come back to his great friend Federico da Montefeltro who had already prepared an abode for him at Castel Durante. Bessarione took with him all his precious books, which he had left in legacy to Venice ( they would become the initial core of the Biblioteca Marciana). He left them with Federico whom he trusted, perhaps he had a foreboding feeling about his trips. Bessarione didn't make it back to Urbino, and died in 1472 in Ravenna. His books, after having been detailed in an accurate inventory, were handed to Venice by Federico in 1474. Is it possible that another of Bessarione's treasured possessions was left back in the hands of his loyal friend, thus becoming the most precious treasure of the city of Urbino ?

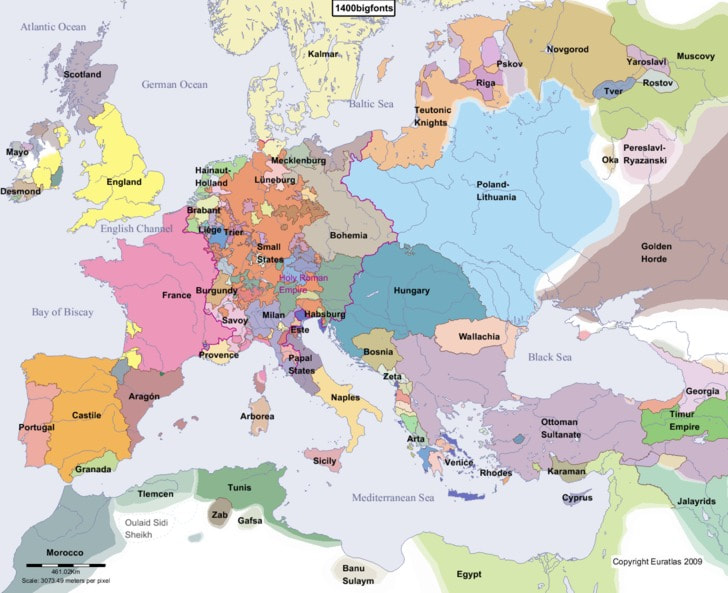

I cannot recommend enough the book by Ronchey if you read Italian. The exegesis is of course much more detailed and complex than I could cram in these few lines. The book analyzes many other contemporary works of art such as Benozzo Gozzoli's Cappella dei Magi, Vittore Carpaccio's Post first published in May 2012 In the past weeks I have been reading a book that I had seen a few years ago but never got to buy. The book is called L'Enigma di Piero ( Piero's Enigma), it was published in 2006 and is by Silvia Ronchey, a scholar of Byzantine History. Ronchey looks back at previous interpretations of The Flagellation, the small painting by Piero della Francesca in the Palazzo Ducale of Urbino and gives her own reading of the masterpiece. I am summarising the content of the four hundred pages of the book here because I see it has not been translated in English and it is a very intriguing read. Ronchey's interpretation is now well respected and takes into account the work of many previous scholars. The painting is one of the big mysteries in art history, and since its "rediscovery" it has prompted a myriad of different exegeses. The Flagellation is the painting where figures were deemed having "some African features" and " thick ankles" and therefore rejected by the envoy of London's National Gallery, in Italy to buy masterpieces for the museum. Its success started later on with a French scholar, Layard, and Degas was the first painter who rushed to Italy to see it after reading Layard's article. Critics soon realised Piero was a major artist and his paintings were then analysed by all the most renown art historians, including Berenson, Kenneth Clark, Longhi, Gombrich, Pope-Hennessy and countless others. The first one to interpret the work in the light of Byzantium's history was Kenneth Clark, and Ronchey proceeds from that idea and enriches the book with a hundred pages of apparatus to support her theory. Historical context In order to understand the real significance of Piero's painting, it is important to look at the complex political and historical situation of Southern and Eastern Europe in the first half of the fifteenth century, when Byzantium was about to fall to the Turkish armies and frenetic negotiations were made to try and save the Empire. The main ambassador of the Emperor in the west was Bessarione, a greek cardinal who, though originally an anti-latinist, had argued in favour of the reunification of the Eastern and Western churches during the Council of Ferrara/Florence as he thought it the only way of obtaining help for the Empire. A crusade organised after this council ended in a complete disaster. The plan was to move the capital of the oriental Empire to Mistra, a city close to Sparta in the Peloponnesus, that was already one of the most prosperous parts of the Empire under the aegis of Teodoro and then Tommaso Paleologo, brother of the Emperor. This would have been a very beneficial move, as Mistra could be an important strategical bridgehead to contast the ever increasing Ottoman empire both commercially and militarily. Mistra was also at the centre of cultural interest as it had been the home of a school of Neoplatonic philosophers which had deeply influenced Humanism, the movement at the heart of Italian Renaissance. One of the major sponsors of this strategy was Pope Pius II, Cardinal Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who canvassed for years in order to organise another crusade. All the leading families in Italy were interested in Mistra: the Gonzaga in Mantova, the Estensi in Ferrara, the Malatesta in Pesaro, the Montefeltro in Urbino. They all had family ties between themselves and with the Emperor ( the beautiful Cleopa Malatesta had been married to Teodoro Paleologo, brother of Tommaso and previous despot of Mistra), they had power and money. Pope Pius II organised a second council, in Mantua in 1459 to try and launch yet another military offensive. Not only he was seeking for the support of these families, but he also tried to involve Venezia, Genova, Burgundy and other countries. Constantinople had, in the meantime, fallen, and the last remaining Emperor, Tommaso, the youngest brother who wasn't expecting to reign, had escaped to Italy with his family. Having decided to personally lead the crusade in order to push all his very reluctant allies, the Pope died in Ancona while getting ready to set sales for the Aegean sea in 1464. The crusade happened anyway, and it was another failure. In a short time the Pope, the last Basileus Tommaso Paleologo and Sigismondo Malatesta, leader of the crusade who caught malaria in Mistra, all died, and with them the hope to reunite the Empire with Rome. The daughter of the last despot of Mistra would then marry Ivan III, great prince of Russia, the new Cesar ( Csar). The ideological legacy of the Empire of Bysantium was going to pass to Moscow, re-enter orthodoxy and be progressively detached by the West. The -failed- unification of the first and the second Rome is the project of which the Flagellation, in Ronchey's opinion, was the manifesto. The analysys of the painting will be in the next post. |

Check the list below to see posts on these subjects.Categories

All

AuthorIlaria Rosselli Del Turco is an Italian painter living in London. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed